Creepazoid Groupie Stalker Meets Cahiers du Poopheads

An Ode to the Extraordinary Ordinary 𝘕𝘠𝘗𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘴 Film Section

[Author’s Note, prior (12/16/2019): I wrote this piece in 2016—the final draft is dated December 5th of that year. It was to be the introduction to a book, a version of which is being published next year by Seven Stories Press, that collected the film criticism of Godfrey Cheshire, Matt Zoller Seitz and Armond White, all of it culled from their time at the alternative weekly NYPress. It was ultimately not included, for rather unpleasant reasons, and the whole experience left me uncertain about aspects of the piece, particularly whether its outlook was too rose-colored and sentimental. I put it away. But I often recalled it fondly, which is rare when it comes to things that I’ve written. I wanted it to see the light of day. And the fact that I conceived it as an “ode”—a tribute to people who mentored me both in print and in person—I think justifies the at times elevated tone. If my emotions about these events are more complicated now, that doesn’t invalidate the place I was at when I composed this essay. I recognize this Keith, and acknowledge he once felt this way. Thanks for reading.]

[Author’s Note, present (11/20/2020): Now that the book is out in the world (full title: The Press Gang: Writings on Cinema from New York Press, 1991-2011), I thought it would be good to repost my rejected intro here on (All (Parentheses)). Former NYPress staff writer Jim Knipfel ultimately got the preamble gig (an excellent choice), and you can read an excerpt from his piece at Literary Hub. Final public thought about this extremely bittersweet project: I learned my intro had been rejected right before the start of one of the final 3-D 120fps screenings of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. I’m sure there’s something pointed and poetic in that. We’ll let the biographers sort it out.]

1.

This is a book about movies. So it's only appropriate to begin with an image. Picture, if you would, a box. Not a perfect square, but an imperfect rectangle, standing lengthwise on a New York City street corner. It's about as tall as an average 12-year-old. It's made of weather-resistant plastic. "Green is its color." (Couldn't resist the Twin Peaks reference…sorry/not sorry.) There's a door on the front. You open it, look inside and discover a stack of newspapers. (Remember those?) Pick one up and ink rubs off on your hands. Hold it long enough and people will assume you’ve just been fingerprinted at the local precinct. There is something, come to think of it, illicit about what you're doing. At the least intensely private. Or that's how it felt to me whenever I picked up a copy of the NYPress.

What is (was) the NYPress? I get that question more and more as the years pass. So, the facts as I know and perhaps rose-tintedly embellish them: The NYPress was (is) an alternative weekly newspaper founded in 1988 by conservative writer Russ Smith. In part, it was positioned as a competitor to the long-established, left-leaning Village Voice, and I'm betting, at this point, that you think you've got the publication pegged. It's the elephant to the Voice's donkey. The red state to its blue. (Funny that the Voice was peddled in a street-corner plastic box of the rouge-iest rouge.)

In truth, the Press defied labels, defied classification, often defied common sense, which gave it that much more of an edge on the Voice—if not in numbers, then in synapse-stoking brashness. Here was a true melting pot, much of it overseen by John Strausbaugh, who edited the paper between 1990 and 2002. Smith had his column "MUGGER" in which he held "rightly" forth on the issues of the week. Other conservative voices included future Weekly Standard editor Christopher Caldwell and Greek journalist/aristocrat Taki Theodoracopulos. But turn the page and you might find a broadside penned by Irish anarchist Alexander Cockburn. Flip a few more and you'd come across one of the nakedly personal confessions of J.T. "Terminator" LeRoy, a teenage maybe-trans former male prostitute who was years later revealed to be a hoax-prone thirty-something female named Laura Albert.

The distinguished (of a kind) contributor list goes on: Soul Coughing frontman M. Doughty ("Dirty Sanchez" pseudonymously). Heartbreaking genius (to some) Dave Eggers. Jonathan Ames, trying his hand at the distinctive, if oft-irritating tweeness that would inform his two cult TV series Bored to Death (2009-2011) and Blunt Talk (2015–2016). Can't forget Jim Knipfel, who worked his way up from Press office receptionist to full-time staff writer (his column "Slackjaw" frequently dealt with the degenerative eye disease, retinitis pigmentosa, he'd been diagnosed with as a teenager). Or Ned Vizzini, the boy wonder who wrote funny, penetrating essays from an advanced adolescent perspective, and sadly killed himself in 2013, succumbing to a lifelong struggle with clinical depression.

I personally recognized how special the Press was after opening an issue and spotting a just-debuted theater column by Claus von Bülow, the British socialite (played with reptilian allure and insidiousness by Jeremy Irons in 1990's Reversal of Fortune) who was accused and eventually acquitted of the attempted murder of his wife Sunny. What shameless insanity! What glorious lunacy! By that point I'd been a regular Press reader for a few years, though I couldn't date first contact except to say it occurred while I was a film production student at New York University. I guess you see enough of those green street-corner boxes and you have to know what's in them. But none of the people I've listed above were my reason for returning to the paper each week. For within this gem of a rag lay another treasure: a nonpareil film section written by Godfrey Cheshire, Matt Zoller Seitz and Armond White.

2.

It's their work you'll find in the following pages, a healthy selection (by editor and fellow Press film section fan Jim Colvill) from the articles they wrote between 1991 and 2010. The book is divided into five parts, beginning and ending, in Parts 1 and 5, with a single voice (Godfrey in the 1991-1995 section; Armond in the 2005-2010 section). In-between are two parts (2 and 4) of two alternating voices (Godfrey and Matt for the 1995-1997 section; Matt and Armond for the 2000-2005 section). And then there's the meat of the book, Part 3, which covers the golden years 1997-2000, when the three of them were churning out lengthy, multifaceted copy of a kind that the pessimists among us would say was too good to last. Being more of an optimist, I'm happy that I recognized a good thing while I had it, and that Godfrey, Matt and Armond's work now has a better chance of living on and inspiring others.

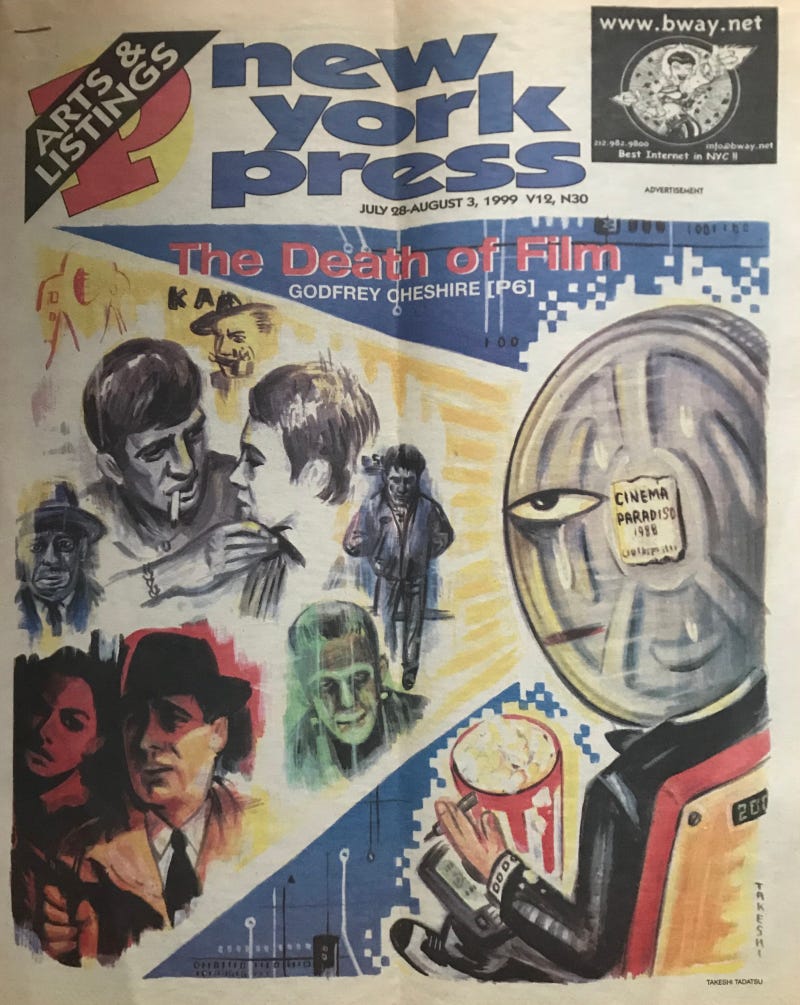

There are many movie reviews in these pages, as well as a number of in-depth feature pieces on film festivals, on specific national movements like the Iranian and Taiwanese New Waves, and on medium-shifting developments such as the rise of digital moviemaking (to the latter, I must note Godfrey's two-part investigation-cum-polemic "The Death of Film"/"The Decay of Cinema" as one of this collection's crown jewels). All of the writing here resists formula. Don't look, in other words, for star-rated consumer reportage, or for binary-prone text that flatters rather than challenges. This is criticism of the sort that W.H. Auden, describing the film reviews of James Agee in a 1944 letter to The Nation: "…belong[s] in that select class…of newspaper work which has permanent literary value."

When I knew them as bylines only, Godfrey, Matt and Armond were icons and inspirations: Three writers who spoke my language, yet never parroted what I thought. The pleasure of their respective prose came from the sense of having my brain rewired each week…and then resisting that. In the somewhat painful (but a good painful!) process, I formed my own sensibility. Godfrey's pan of Paul Thomas Anderson's '70s-porn-groove Boogie Nights (1997), for example, includes a provocative passage on one of his consistent bêtes noirs. "…It seems to me," he writes, "that the critical tarantella over Boogie Nights has quite a bit to do with Ol' Scratch himself: television. Put simply, critics have now spent several decades trying to distinguish and defend what might be called the salient esthetic values of film to a public that knows and cares little of said values, having been thoroughly conditioned by the newer and more pervasive electronic medium."

As one who then (and still now) considered television as worthy of analysis as movies, and who often spoke of the mediums in the same breath, I chafed at this passage. There was plenty wrong with Boogie Nights (I was never much of a PTA fan) that we didn't need to drag the poor ol' boob tube into it. But the argument I had in my head—indignant twenty-year-old me standing up to a nebulous image I concocted of Godfrey (I pictured him as a stuck-up, bespectacled, Brit-accented professorial type, a far cry from the Southern U.S.-raised, semi-punkish, rock music-loving reality)—was a healthy one, helping me to acknowledge an alternate perspective while still standing my ground. A good lesson to learn early on: A critic can be confident without remaining so completely entrenched.

I'd have similar impassioned "discussions" with Matt and Armond. Since Matt and I were closest in age, I might, for example, find myself commiserating with my image of him over a childhood favorite. "But the excitement surrounding Star Wars was more than a fad," he writes in a remembrance piece about George Lucas's original trilogy. "This was more like a secular, consumerist cult—a wholly invented capitalist religion aimed at, and perpetuated by, millions upon millions of goggle-eyed children. At the risk of forever typing myself a Generation X kid critic, I freely admit that I memorized the scripture, chapter and verse." Ditto, I'd think, while head-nodding vigorously.

Or I'd find certain presumptions rooted in my white suburban middle-class upbringing exploded by Armond, whose prose was frequently enflamed by righteous rage against those who would, as a matter of historically-ingrained course, denigrate his and others' humanity as African-Americans. From his review of Titanic (1997): "'White people would rather see themselves die than watch black people live,' I heard a film student surmise after reading numerous negations of Amistad and media hype for Titanic. … If it is a race thing—indeed, the predominantly white critical fraternity embraces Titanic as a propensity toward the safe, affectless mode of apolitical culture—then that film student's observation correctly pinpoints a dreaded development: modern movie esthetics have become inescapably aligned solely with the desires of the empowered class that controls Hollywood and the media." Shattering. Can I pick up the pieces, I'd think, after reading such a broadside, and be better? Are there, indeed, pieces to pick up? Maybe this is more a shedding of the skin—peeling away layers, delving toward a more enlightened core. (A constant forge, to be sure.)

Cinema, then in the midst of one of its many media-declared death throes, was alive and well as long as it inspired this quality of writing: individual, distinctive, with that air of authority that still allowed room, in perpetuity, for disagreement and argument. It was all I could do to measure up, and I doubted any of my attempts at analytic prose (for the Golden Age of the NYPress film section coincided with my slow realization that criticism was my true metier) ever would. I'd surely have gone pale and done a fanboyish swoon if you'd told me then that I'd one day befriend my heroes. But I did. And there's a story or four: The mortal meeting the masters and discovering, of course, that they are fellow men.

3.

Should I call them the Three Amigos? Godfrey once told me that Strausbaugh termed them "Cahiers du Poopheads," a derisively dung-inflected reference to the famed French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. (Their own editor had little use for them, which was perhaps a blessing in disguise—fewer eyes, more freedom.) I can't recall if Godfrey related this anecdote the first time we met, or some time thereafter. It was appropriate, anyway, that he was the first of the NYPress three to whom I reached out, since he was the paper's initial film critic, and often acted, to my mind, as the sobering counterbalance to Matt's youthful brashness and Armond's fiery zeal.

In 1996 (my sophomore year in college), I read an inspiring NYPress article entitled "Why I Make Movies," written by the great actor Tom Noonan, who was best known for playing chillingly composed serial killers like Francis Dolarhyde in Michael Mann's Manhunter (1986) and Ripper in the John McTiernan-Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle Last Action Hero (1993). But he was also an accomplished playwright and filmmaker with two directorial efforts (1994's What Happened Was… and 1995's The Wife) under his belt. Tom included his email address at the end of the article and I wrote to him, which eventually resulted in my working on his latest play (Wang Dang), as well as its unreleased 1999 movie adaptation. Tom later told me that Godfrey had commissioned the piece, and I worked up the courage to ask if he might introduce us virtually. Tom did so, and Godfrey and I planned to meet outside his apartment in Greenwich Village and go to lunch.

What I mostly remember from that first meeting is apologizing for liking Star Wars: Godfrey had gone on record about his disdain for the film and its offshoots in an article (not included in this collection) titled "Why I Hate 'Star Wars'." He confessed that his preferred headline was actually "The Case Against 'Star Wars'," but Strausbaugh wanted something punchier—clickbait before its time. For all my nervousness, Godfrey and I hit it off, and from then-on he frequently invited me as his guest to press screenings.

It was at one of these advancers (for 1999's blissfully forgettable indie gay rom-com Trick, starring Neve Campbell's brother Christian) that I first crossed paths with Armond. I swear I didn’t plan to have his collected book of criticism The Resistance: Ten Years of Pop Culture That Shook the World (1995) under my arm, but I've found the universe likes playing such jokes. Godfrey caught sight of him as we entered the screening room. "Hey, Armond," he said. Then, gesturing to me, "This is Keith. Look what he's reading." Sheepishly, I held up my hardcover copy of the book. Armond smirked delightfully and said, "Heh…a man of taste." Blessings be upon me. Where's the fainting couch?

Only Matt remained. Then I’d have ascended Olympus and met all the gods. That finally happened at a press screening of Bringing Out the Dead (1999), Martin Scorsese's then-latest, a thriller about ambulance drivers (led by Nicolas Cage) overlaid with Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader's multifacetedly muddled perspectives on Christianity. Godfrey was there (I was his guest as usual). So was Armond. And standing near the screening room entrance was Matt, who I recognized from his TV critic author photo for the New Jersey newspaper The Star-Ledger (he had then, as now, multiple writing duties for numerous publications).

Godfrey again acted as go-between, and I was soon yammering on and on like a lovesick admirer. (I recall Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992) being a main point of discussion.) Matt was indulgent to the point of sainthood, even after I split from Godfrey at the end of the movie so as to ride home on the subway with my new acquaintance. Thinking back on it, my cultish behavior was nosy at best, unnerving at worst, and Matt seemed to be in one of those get-me-out-of-here mindsets by the time the train pulled into his stop. He insists to this day that he remembers that first meeting with nothing but fondness. But this is my version of events, so…yeah, I was a creepazoid groupie stalker.

4.

Friendships still blossomed with all three, though the risk of interacting with your idols in the flesh is that the romanticized glow fades that much more quickly. Now the arguments I had weren't with constructs, but the real deal. And film critics in disagreement are an often prickly bunch. I well remember the first time Godfrey and I arrived at an impasse—when he told me his top ten movies of the 1990s would most definitely include Steven Spielberg's Amistad (1997) (which I hated at the time, and which, though I've softened on it since, is one of the very few of that great director's films to still give me trouble) and I visibly and verbally bristled.

Godfrey's face became stoic and the friendly tenor of our conversation suddenly shifted. We weren't yelling at each other, exactly, but there was an edge to how we were talking that I hadn't experienced up to that point, not even in our most heated imaginary debates. We eventually settled back into a more even-tempered groove, and this also happened to be the same meeting where Godfrey offered me some very friendly feedback on a review I'd written of Stanley Kubrick's final feature Eyes Wide Shut (1999). But it was still an upsetting situation, and it's upsetting remembering it, because it revealed how easily differences of opinion can test the bonds of friendship. It truly is never just a movie, to anyone. (You can read Godfrey's original review of Amistad in this collection—he makes a superb, compelling case for it.)

A comical variation on this incident happened a few years later when I went out to dinner with Armond after a day in which I'd seen David Lynch's masterful surrealist melodrama Mulholland Drive (2001) and Bruce Weber's comparatively forgettable personal essay doc Chop Suey (2001). Armond was quick to lambast Weber's film as small potatoes, especially in comparison to the Lynch, which he termed, with no hesitation, "extraordinary." (It's nice when we critics agree.) But while we were eating I mentioned that I quite liked Baz Luhrmann's hyperactive musical romance Moulin Rouge! (2001), which I knew Armond hated. (From his review in this collection: "Baz Luhrmann is a trash-besotted gnome. Where do you start (or stop) listing the many incandescent movie-musical moments that are superior to his.")

Armond's face actually lit up—I'd describe it as shock and delight intermingled, as if he were responding to the film critic equivalent of morning "Reveille" at Parris Island. He reached for a ketchup bottle and brandished it threateningly. "OK…now we gotta fight!" he said. There was an uncomfortable pause. Then both of us laughed, actually finding some good humor in our disagreement. Though I also recall quickly changing the subject, so as not to push any more buttons.

By the time I went to see Bryan Singer's reworking of the Man of Steel, Superman Returns (2006), with Matt, I'd learned to bite my tongue a bit more. I could sense Matt was enjoying the film much more than I was, and this was in the aftermath of a devastating personal tragedy that he references in one of his later reviews, so I was even more inclined to tread lightly. I regret that now; I really should have spoken up and engaged in some healthy debate. At our lowest moments, it's frequently community (or a basic sense of communality) that sustains us, even if there's some edginess or irritability in our interactions. Probably lets us know we're alive.

Matt still penned a lovely review (the last he wrote for NYPress) of Superman Returns, and I certainly don't feel like disputing the sentiments that close his piece: "The film's most haunting scene finds Superman floating above the earth, eavesdropping on layers of conversation, then becoming overwhelmed and shutting them all out. He could be a two-fisted cousin of the angels from Wings of Desire. He feels guilt over needing not to be needed, if only for an instant. He's an extraordinary ordinary man—the better angel of our nature."

5.

Extraordinary ordinary men. I suppose that's as good a description as any of Godfrey, Matt and Armond. We are each of us messes of contradictions, and art is but one of the methods we use to give some order to the chaos. How far should I go into the chaos (at first sustaining, ultimately destructive) that consumed the NYPress? How, for instance, Godfrey was unceremoniously let go from the paper at the end of the year 2000 for reasons that still seem murky? Or how this robust alternative weekly became a paler and paler shadow of itself as editorial hands changed, and page and word counts shrunk? Suffice to say it wasn't a pretty picture, though Matt and Armond (the latter of whom hung on until the very bitter end) still managed to do good work, even if the strain of inevitably changing tides was often clear.

Nothing lasts forever. But we still have our lives to live and our experiences to sustain us. And since memory is not a corpse, the past can become present again. So I'd like to close by returning to that screening of Bringing Out the Dead, where the three men I knew for so long in prose now surrounded me in person. There I sat with Godfrey to my right, Matt and Armond to my left, watching Scorsese's modern morality tale unfold, barely able to pay attention because I was giddy at the minds, at the people, that I knew surrounded me. The light that so often emanated from the movie screen (cultivating thought, countering loneliness) now radiated from the audience. We were each ourselves, but we were also one. Equals as only humans who dream of bliss—cinematic and otherwise—can be.