The stars of Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy find the feeling in fantasy. By Keith Uhlich

A British man and a French woman meet in Italy. They’re complete strangers: He is an academic promoting a new book on art reproductions; she is an antiques dealer intrigued by his studies. They go on an afternoon excursion, driving around the countryside, visiting a museum. Then, during a stopover at a café, they suddenly start to act like husband and wife. By the end of this grand day out, they have become a bickering but loving married couple of 15 years — strangers no more, and plausibly so. The story is true. This actually happened.

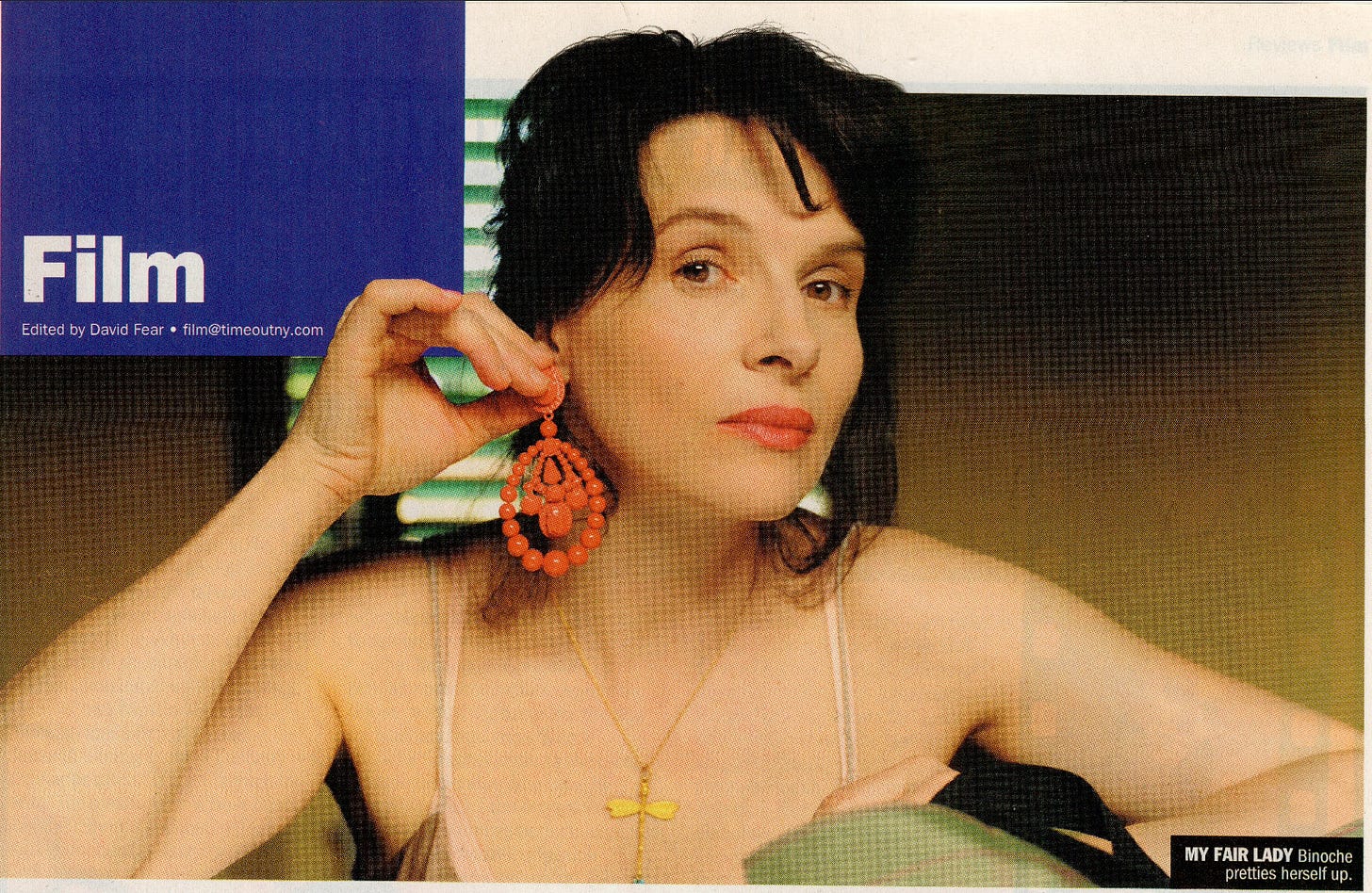

“And then he asks, ‘Do you believe me?’” says Juliette Binoche, sitting in a Manhattan hotel as she recalls how acclaimed Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami initially related what would become his playful and profound romance Certified Copy. “I was taken aback for a second because how Abbas was telling the story was like being on a roller coaster. I said, ‘Yes, I do believe you.’ And then he said, ‘It isn’t true.’ I couldn’t stop laughing because he really caught me. I couldn’t get over how he’d worked on my beliefs.”

There’s a sublime glint in the actor’s eyes as she finishes this anecdote; it’s as if the director’s tall tale of an antiquarian (played by Binoche) and a scholar (opera singer William Shimell, making his movie debut) on a role-shifting journey around Tuscany has unearthed entirely new facets of her imagination. “This was completely different from Shirin,” she says, referring to the 2008 experimental feature on which she first worked with the director. In that film, Binoche was one of more than a hundred actors whose reactions to offscreen stimuli were recorded and then edited together to make it seem like they were watching a movie. “It was more about directorial manipulation,” says Binoche, “where Certified Copy was more of a collaboration because it revolved around this woman’s experiences. But both are, in their own way, about questioning reality.”

There’s plenty of precedent in Kiarostami’s influential body of work for Certified Copy’s spirited inquiry into narrative truth. (See his metafictional masterpiece Close-Up, about a cinephile who impersonates a famous director.) But though the movie unsurprisingly begins in the realm of ideas — the opening scene is a lecture about “authenticity” in art — it quickly moves into more impassioned, emotionally frank terrain. Anyone who thinks the filmmaker is merely a removed, reserved observer of his characters will, in fact, be shocked by such rawly affecting sequences as a late-act bilingual shouting match, in which the duo draws on fabricated (or perhaps factual?) memories to one-up each other.

“This woman could imagine herself with this man,” Binoche says, when asked about the film’s fervent emotional palette. “So she pushes him to define himself. And William’s character often retreats, because he has a controlling kind of manner — as men often do. The film is attempting to explore the different ways a man and a woman handle life and their own feelings, and I think it goes into more feminine territory than Abbas’s other movies. The antiques dealer is like the leader of this journey; the academic is more often following and reacting to her.”

Reached by phone at his home in Cornwall, England, the polite, frequently self-deprecating Shimell (whom Kiarostami cast after directing him in a stage production of Cosi fan tutte), defers to his costar. “A good deal of how I played the role was in reaction to Juliette’s performance,” he says. “I’d like to say it was an in-depth portrayal, but I just wasn’t experienced enough to be able to do that. I was surviving from scene to scene. In a way, I felt that this was my character in the film, that he was constantly responding to what she said and to her emotions rather than contributing very much of his own.”

Binoche’s role has more frequently been singled out for praise by reviewers, and she took home an award at Cannes. Yet Shimell’s reactive efforts are crucial to the film’s success. (It’s no mistake that he’s granted the extraordinary final shot.) Indeed, as the story progresses toward an ambiguous, yet deeply moving finale, Kiarostami seems to be intentionally aping a certain strain of two-hander cinema (Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage in Italy and Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage are two apparent touchstones) as a way to further explore the idea of what a copy really is.

“We didn’t talk about his influences or intentions, really,” Binoche says in reply to this reading. “I personally don’t think Abbas wanted to copy any films that came before. The film’s theme really comes from life. Do we live copies of things we once thought about? Do we belong to another reality? Where is reality? This is a kind of three-dimensional cinema without the glasses. Each of us has a whole life, or lives, that nobody else knows about. To me, this film is Abbas’s testament about relationships.”