★★★☆☆

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard. 2010. 101mins. In French, with “Navajo” subtitles. Catherine Tanvier, Christian Sinniger, Jean-Marc Stehlé.

Artist? Poseur? Genius? Asshole? There are several Jean-Luc Godards on display in the controversial Film Socialisme, which scuttlebutt says might be the French New Wave auteur’s final provocation. This experimental video feature, segmented as a triptych, generated an expected stream of hosannas and damnations after its 2010 Cannes premiere. Viewed outside the festival bubble, however, it plays as a profoundly mixed bag. Yes, the so-called “Navajo” subtitles that graced the film’s Croisette debut are still in place, which means that, instead of having the mostly French dialogue translated into full English sentences, you’ll see only intentionally ungrammatical fragments (“aids tool forkilling blacks”). These garbled captions have their own strange poetry — think of them as koans that complicate rather than simply decode what we’re seeing — and they fit with the Tower of Babel–like atmosphere the writer-director is cultivating.

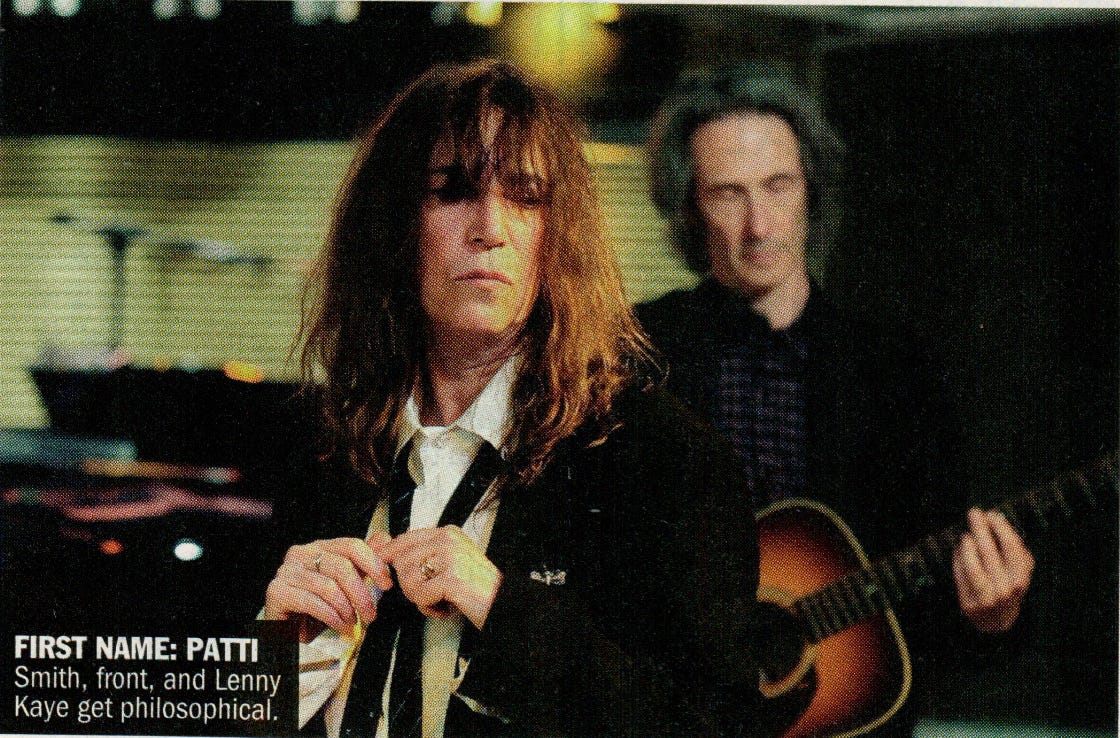

As to the movie’s three sections, the best comes first, as an eclectic “cast” of characters (among them philosopher Alain Badiou and musician Patti Smith) pontificate their way around a lavish Mediterranean cruise ship. Godard brilliantly captures this bastion of capitalism with all manner of cameras, from hi-def to cell phone, making the ship seem like a narcotized hell. And save for some muddled swipes at Zionism — a miserly black hat called Goldberg has his name translated to “Gold Mountain” (haw haw) — he’s fully on his game. The remaining parts (number two is set at an idle French gas station, while the third is a rapid montage that recapitulates the film’s themes) come alive only sporadically, as in a striking moment when the video image is suddenly manipulated to resemble a Renoir painting. Beyond that, this is Godard in crotchety virtuoso mode, treading through territory that previous works like La Chinoise (1967) and the Histoire(s) du Cinema (1988–1998) have explored with more profundity and far less peevishness.—Keith Uhlich