Greta Garbo never made a color film, but in life she was an aesthete who needed to be surrounded by what she called “my colors”: rose, salmon, green, red, pink. Love of these colors influenced the paintings she collected, which hung on the walls of what for nearly 40 years was her sanctuary, floor five at the Campanile, a secluded building in Manhattan at 450 East 52nd Street that overlooks the East River. Garbo purchased this apartment in 1953 for $38,000, and though she liked to travel in the summer months, in the autumn and winter she lived as a kind of hermit about town in Manhattan with this apartment as her base.

By the time she purchased her apartment in the Campanile, Garbo was 48 years old and had pretty much given up on appearing in movies. During her career as a top star at MGM in the 1930s, enough of her money was saved in stocks and bonds that, if she lived carefully, she did not have to work again. During all the second half of her life in Manhattan, Garbo was pursued by photographers, and interest in her only intensified as her classic films like Camille (1936) and Ninotchka (1939) played at repertory theaters and on television. She never married or had children, and there seemed to be some kind of mystery about that, at least to some people. But Garbo was a very modern sort of person living her life the way she wanted at a time when there were different expectations for women.

“I want to be alone,” she says in Grand Hotel (1932), but Garbo always clarified that in life she only wanted to be “let alone,” a key distinction for her. She had a small group of friends and family that she trusted, and her sense of propriety, which is one of the few non-modern things about her, meant that avoiding any appearance in the newspapers was a matter of great concern. This was one of her biggest difficulties because the appetite for any information about her life was so insatiable that she couldn’t go to a club or a restaurant or a fashion house without it getting written up somewhere.

Garbo’s great gift as an actress is her ability to go to extremes of joy or sorrow, and at her best she is so open, so bravely unprotected, that rare and complex insights about life seem to rise up naturally from the depths of her beautiful Helen of Troy-level face. In the second half of her life in New York, she was still drawn to extremes, but this was most evident in the paintings she hung on her walls. She owned three Renoirs, and she also owned a Pierre Bonnard called “Les Coquelicots.” Speaking of this Bonnard painting to Donald Reisfield, the husband of her niece Gray Reisfield, Garbo told him, “Just before he painted that, he thought color had turned his head and he was sacrificing form to it. Look at it. It makes you feel like you’ve had a glass of champagne — the brink of dizziness.”

In her best work on screen Garbo was always on the brink of dizziness, at some height of happiness or grief where she might pass out and we might pass out with her, and those extremes were reflected in her apartment in the Campanile, her kingdom, which she put together with the thoroughness of J. K. Huysmans’s dandy in his classic 1884 novel Against Nature. “In her later years,” said Donald Reisfield, “when the apartment became almost her entire world, Garbo would jokingly say, ‘How the mighty have fallen,’ but she was quite content to be alone, she said, with her friends, the paintings she had so carefully chosen.”

“When she moved into high gear and wished to be her most enchanting persona, you were then doomed to be swept inexorably into the vortex of her charm,” said Reisfield. “Doomed is not the exact word, however. Exhilarating it was to be in her orbit, to be enveloped by that wonderful sense of humor, that rich mellow voice and above all that refracted view of the world.” Garbo saw things differently. She was in touch with something profound, some depth of knowledge, and this is why all of her movies are worth seeing again and again, to watch that knowledge light up her face teasingly, ironically, tenderly, angrily, and yes, tragically.

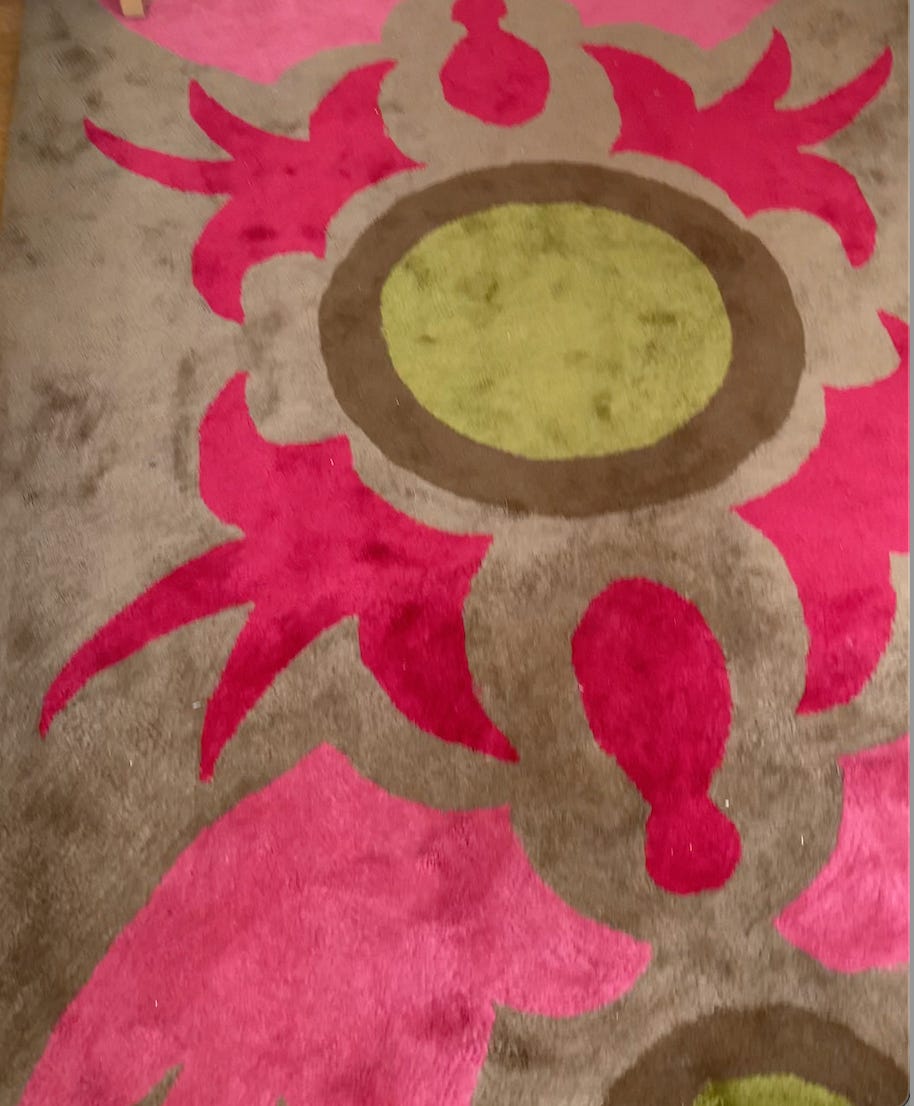

But her family has emphasized how impulsive and jolly Garbo could be, and her friends like Sam Green and David Diamond said that she could be a very good listener. Diamond remembered being in her living room and suggesting that they read aloud from King Lear or an Ibsen play, and Garbo was up for such things as long as they weren’t premeditated and they tickled her fancy. Above all, Garbo was a gender-fluid pathfinder who delighted most in childlike games and scorned the adult world of responsibility. The carpets she designed for her apartment, which are still there today, are called “Birds in Flight,” and that’s what she was. In her movies, she could be like a severe eagle, or like a frightened deer, but in her rich afterlife, the life she chose at the Campanile so far east on 52nd Street, she was a hummingbird: now you see her, now you don’t.

Garbo was out and about every day in Manhattan walking or “trotting” as she called it practically all the way up to her death in 1990. The apartment at the Campanile was left to her niece Gray Reisfield, who kept it as a pied-à-terre until 2017, when it was sold to John and Marjorie McGraw of the publishing house McGraw-Hill after a lively bidding war presided over by Brian K. Lewis, who is now handling the sale of the apartment for the McGraws, who live at this point in New England. The “Birds in Flight” rugs are still on the floor, and the knotty pine paneling that Garbo favored is still there; best of all, her bedroom has been kept the same, with pink Fortuny silk on the wall above the bed and green and gold carvings that came from a design that Garbo’s family had used in Sweden, where she is now buried.

The fate of the Garbo apartment hangs in the balance. It sold for 8.5 million in 2017, and the asking price has gone down from that (the original price had been 5.95 million). The McGraws are Garbo admirers, and hopefully a new buyer will preserve some of the features of the apartment, particularly that pink Fortuny silk above her bed. If I had unlimited money, I would buy the apartment and offer an “I want to be alone” sabbatical for writers to work for two-to-three months on a novel or a play, perhaps with regular showings of Garbo films several times a year. Lewis was kind enough to let me see the Garbo apartment and get a sense of the light she would see from the windows and the views of the river, and for a Garbo-lover and admirer like me this was a very moving experience.

Maybe everybody would like to get away from it all, or have a private world of their own, as Garbo did in the second half of her life, which was devoted to contemplation and making sense of what had happened to her as a young woman, when she became the most famous and sought-after movie star on earth. Her friend Sam Green introduced her to transcendental meditation, and she practiced this faithfully, though she did admit to him that she had trouble emptying out her mind.

Yet what is the most famous image of Garbo? The last close-up of Queen Christina (1933), where her director Rouben Mamoulian instructed her to make her face into a blank sheet of paper that every member of the audience could write on; this was a moment of Zen, or an attempt at it. That was her goal, first as an artist and a symbol in movies, and then by herself in her apartment on 52nd Street, with her paintings and her colors, with the people she loved and the people she loved in remembrance, like her film director mentor Mauritz Stiller and her beloved sister Alva, who died young.

Garbo is so often thought of as a tragic figure, or a woman of melancholy, but that is not the full story. “Just two weeks before her death,” Donald Reisfield said, “I turned aside a question she put to me by asking another: ‘Were you ever very happy?’ After a pause there was a resounding ‘Yes’ — Joyce’s 50 pages of ‘yes’ condensed in a word. It was spoken with directness, with those still clear blue eyes looking straight into your soul, an almost mystical affirmation of 84 years.” Surely some of that happiness came to Garbo on the fifth floor of 450 East 52nd Street, which is still for now a shrine to an artist who sets an inspiringly free-thinking and transcendental example.