Lincoln Center’s tribute to nouvelle vague director Eric Rohmer surveys a master of words (and images). By Keith Uhlich

Imagine a young couple frolicking in the surf on a sun-dappled beach in summer, waves lapping the shore. Their romantic idyll is as tactile as their sweat-flecked bodies, which the camera lingers over with observant tenderness. A moment later, they lie in bed, gazing longingly at each other, blissfully content. Words aren’t necessary; looks will do.

This is the pitch-perfect opening of Eric Rohmer’s delightful romance A Tale of Winter (1992), just one of the many titles screening in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s posthumous tribute series, “The Sign of Rohmer.” The eldest member of the French New Wave is not usually thought of for his expressive visual talents. He’s better remembered as the chatty-cinema poster child, whose characters, like the bored secretary Delphine (Marie Rivière) in Summer (1986), go on at length about crises that could kindly be described as bourgeois. Yet Rohmer keeps us interested because of his inimitable ability to make two people conversing as cinematically stimulating as any action scene.

Several sterling shorter works (“The Bakery Girl of Monceau”; Suzanne’s Career) and features (La Collectionneuse, The Sign of Leo) preceded the film that sealed Rohmer’s rep as a wordsmith. In My Night at Maud’s (1969), a pious Catholic engineer (Jean-Louis Trintignant) has his moral convictions shaken, but not broken, by a smart and sexy divorcée (Françoise Fabian). Its centerpiece is a lengthy, nighttime heart-to-heart that touches on everything from l’amour to Pascal’s wager, and the words carry you along like a river’s current. Yet the camera is always in the right place, perfectly capturing and emphasizing Fabian’s lithe sensuality and Trintignant’s shift-’n’-strain rigidity.

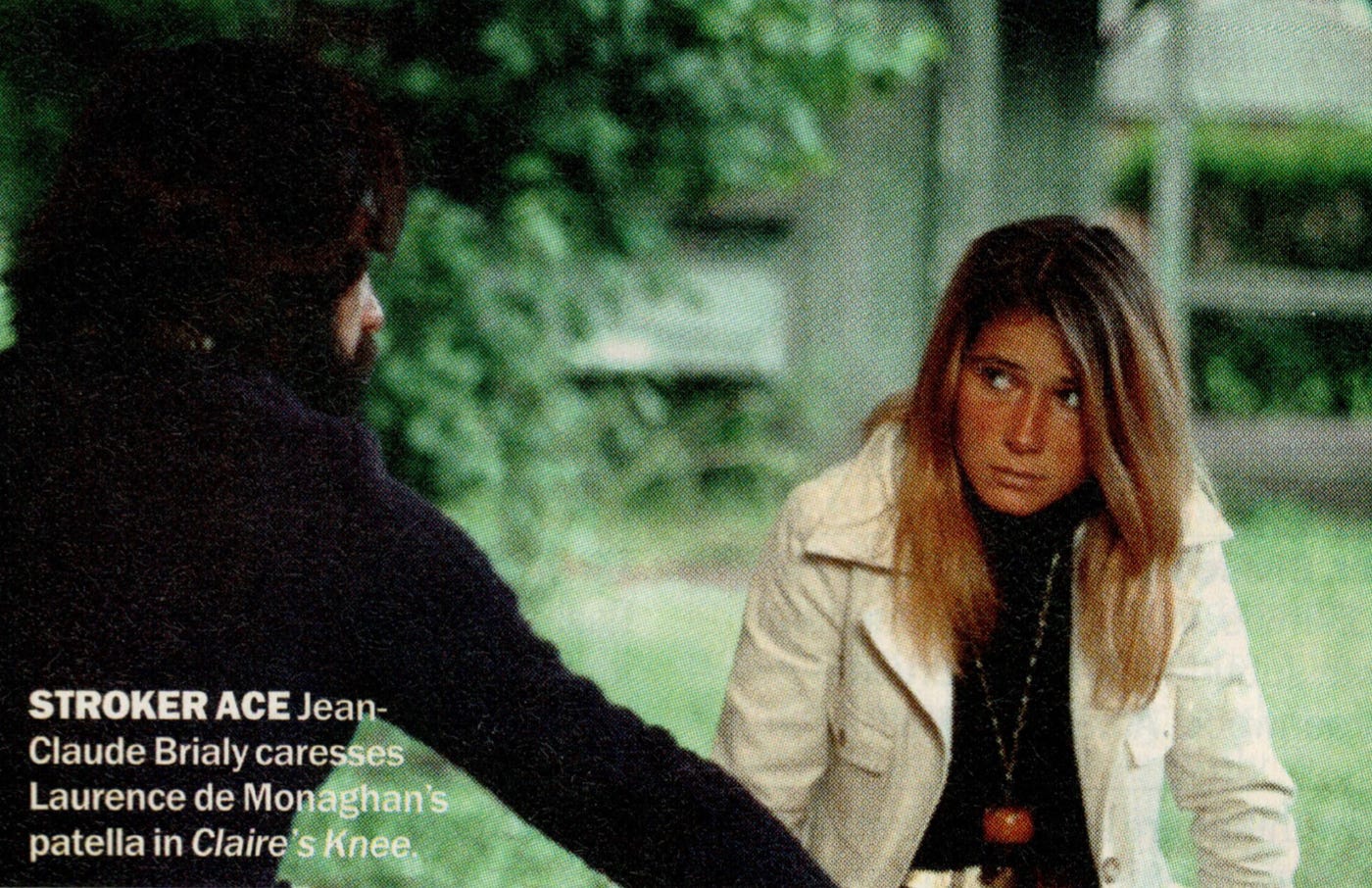

There is no such thing as an expositional scene in a Rohmer film; every line of dialogue, and every corresponding picture, is essential to the whole. Claire’s Knee (1970) is made up almost entirely of pastoral images of diplomat Jerome (Jean-Claude Brialy), talking through different scenarios that end with him caressing the knee of the eponymous teenager (Laurence de Monaghan). When the moment of truth comes, all the spadework done by the writer-director suddenly shifts into sublime focus.

There are similar points of clarity in almost every one of this incomparable artist’s movies, though they never tie things up with a bow. They’re not even necessarily conclusions. The epiphany comes first in A Tale of Winter; the story then follows lonely hairdresser Félicie (Charlotte Véry) desperately trying to reconstitute her revelation. And the stylized Holy Grail adventure, Perceval le Gallois (1978), denies closure altogether. The quest of the tale’s Arthurian hero (Fabrice Luchini) is quite literally endless. Rohmer’s cinema lulls you with heady wordplay, envelops you in precisely filmed spaces. And every so often, like the miracle of nature Delphine witnesses in Summer, it leaves you suddenly breathless, elated and enlightened.