Pity the poor Paramount logo. All the previous Indiana Jones movies graphic-matched the studio’s snow-capped peak with mountains and molehills. At the start of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, the summit is quickly bypassed, sandwiched in-between a Disney castle and the Lucasfilm crest, neither exuding the force of the visionaries-cum-megalomaniacs that christened them. Welcome to the wonderful world of IP, where the memory of what names meant is the only currency.

This sorry state of being applies equally to imagery and icons: Harrison Ford first appears not as his present-day self, but as a de-aged avatar that, even at its most convincing, comes off like a skin-graft simulacrum. It’s the tenor of the voice; the intonations are older than the extravagant deepfake from which they emerge. Scorsese got around the limitations of fountain-of-youth tech in The Irishman by treating it as a Powell-Pressburger-esque thematic tool akin to The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp’s nationalist lampoon makeup effects. And the mind reels at what Spielberg might have made of the modern digi-palette here, considering Dial of Destiny is, in abstract, about a person more existentially outside their time than ever before.

Steven stepped away during development, of course, replaced by James Mangold, the title of whose 2006 MoMA retrospective, “A Work in Progress,” never fails to make me chortle. At best, he’s fine. At worst, well…Knight and Day is there for you to torrent whenever your self-loathing’s in the red. This is the guy who claimed Ozu inspired his work on The Wolverine, and I’ll admit, there were a few moments in Dial of Destiny (in its later, Sicily-set scenes) where I fleetingly thought the movie was cribbing from Rossellini’s Journey to Italy. Unsurprisingly, this proves to be more a shallow nod to the past than an actual deep grapple. The mouth-agape awe of Spielberg’s direction, which at its best communicates the weight of what came before in the most sublime shorthand, is sorely missed.

Instead, we get prosaic bloat. This is the longest Indy installment at 154 minutes, and every second is felt. The opening alone, set during the waning days of Hitler’s reign, takes up a hefty chunk of the runtime, and it doesn’t help that it’s mostly a much less effective rehash of the train chase prologue from the great Last Crusade. Incident and expositional info pile up: “Younger” Indy and his friend Basil Shaw (Toby Jones) are initially after the Lance of Longinus, the spear that pierced Christ’s side (and which Neon Genesis Evangelion already utilized for maximum mindfuckery). But their attentions soon shift to the Antikythera, a two-piece dial created by the Greek mathematician Archimedes with the purported power to pinpoint fissures in time.

A low-level scientist named Jürgen Voller (Mads Mikkelsen) bedevils Indy across this era and the one — post moon-landing 1969 — in which the film is primarily set. Dr. Jones ’69 (nice!) is old and alone, living in a rundown Manhattan apartment building teeming with Beatles and Bowie-obsessed hippies. He’s soon to retire from an unrewarding post at Hunter College and his marriage to Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen) is on the rocks because, well, all you Mutt Williams fans can wait to discover why that particular apocalypse is occurring now. Into the sulking archaeologist’s life strides Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), Basil’s now-grown daughter, the wit-cracker to Indy’s whip-snapper. Globe-hopping adventure ensues (as much as London soundstages, COVID protocols, and floor-to-ceiling green-screens allow for, anyway), leading to a climactic personal reckoning much more important than the objects being pursued.

Indiana Jones may be the one who belongs in a museum by now, but credit where it’s due to Ford for giving him a weary complexity that’s infinitely more interesting than the movie housing him. The best moments of Dial of Destiny are all his, and also Allen/Marion’s, whose appearance alongside Ford here works emo-gangbusters even though it’s conceptually weighed down by being a role-reversed redo of one of the five-film series’ most iconic sequences. Mainly because it’s two performers, as they are, just being, in this moment.

The IP methodology, of course, is anything but this moment. Resurrect then because it’s better than now. And much easier to sell. “It’s called capitalism!” quips Helena after explicating her I-steal-you-steal-we-all-steal ethos to a Moroccan cantina’s worth of black marketeers. I wouldn’t be surprised if Waller-Bridge came up with that bon mot on the spot, though the sarcastibitter glance she shoots Ford’s way suggests she knows deep down how toothless the observation is in this corporatized context.

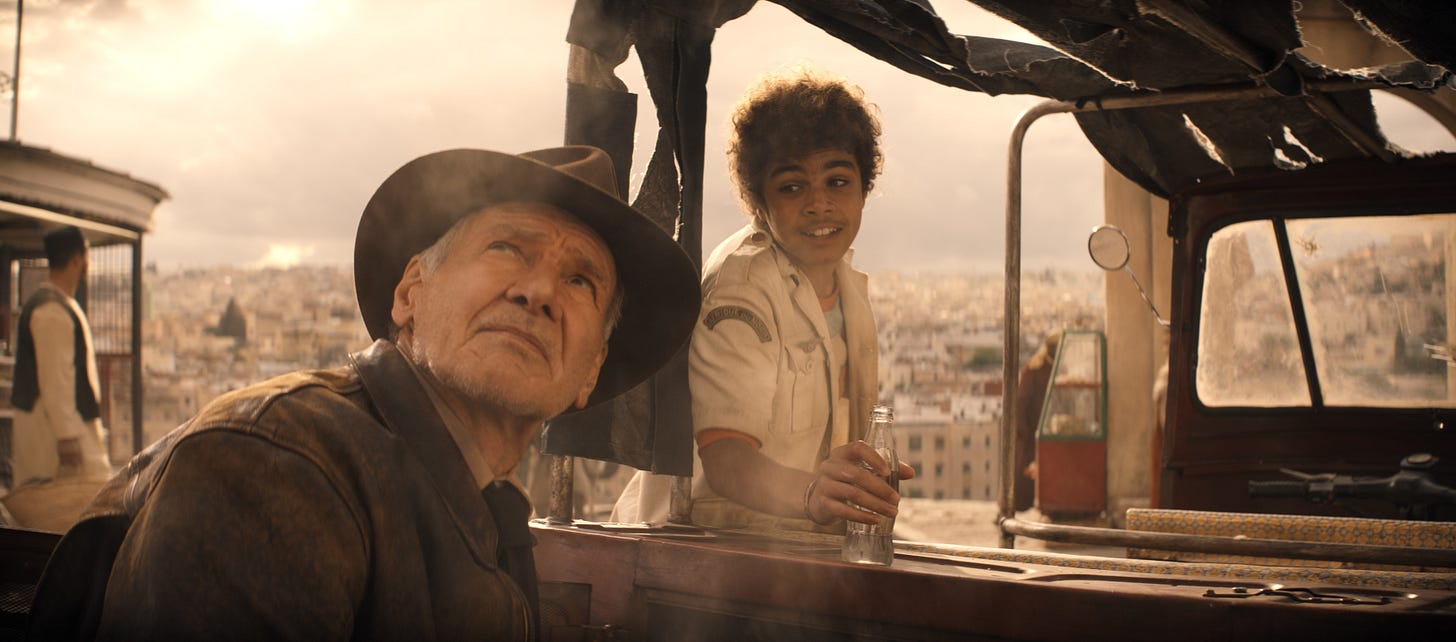

Amuse yourself failing all else, I guess. That certainly seems to be what most of the seasoned performers are doing (I nearly lost it when Mikkelsen’s Voller says “I don’t want to go back to Alabama!” like a spoiled prep-schooler), while relative newbies like Shaunette Renée Wilson as one of Voller’s lackeys and Ethann Bergua-Isidore as Dial’s version of Temple of Doom’s Short Round delusively treat these pop-cultural table scraps as if they were a Michelin-starred banquet. That Ford is the one who seems most engaged here is perhaps the biggest surprise, given how gruffly above-it-all he can be onscreen when disinterested. A glimmer of hope within the plutocratic morass: His affection for Indiana Jones can’t be bought, even though he was.