Werner Herzog digs 3-Deep in Cave of Forgotten Dreams

It began with a book. While passing a store display window, a young German boy found his attention captured by a text with the image of a horse on the cover. But this was no ordinary horse — it was a richly detailed cave painting from the prehistoric French cavern at Lascaux. It fascinated the youngster, so much so that he saved up his money for months and would pass by the store each week to make certain the book was still there, convinced it was the only copy in existence. After finally purchasing it, he found the images inside stimulating. An artistic conscience had been sparked.

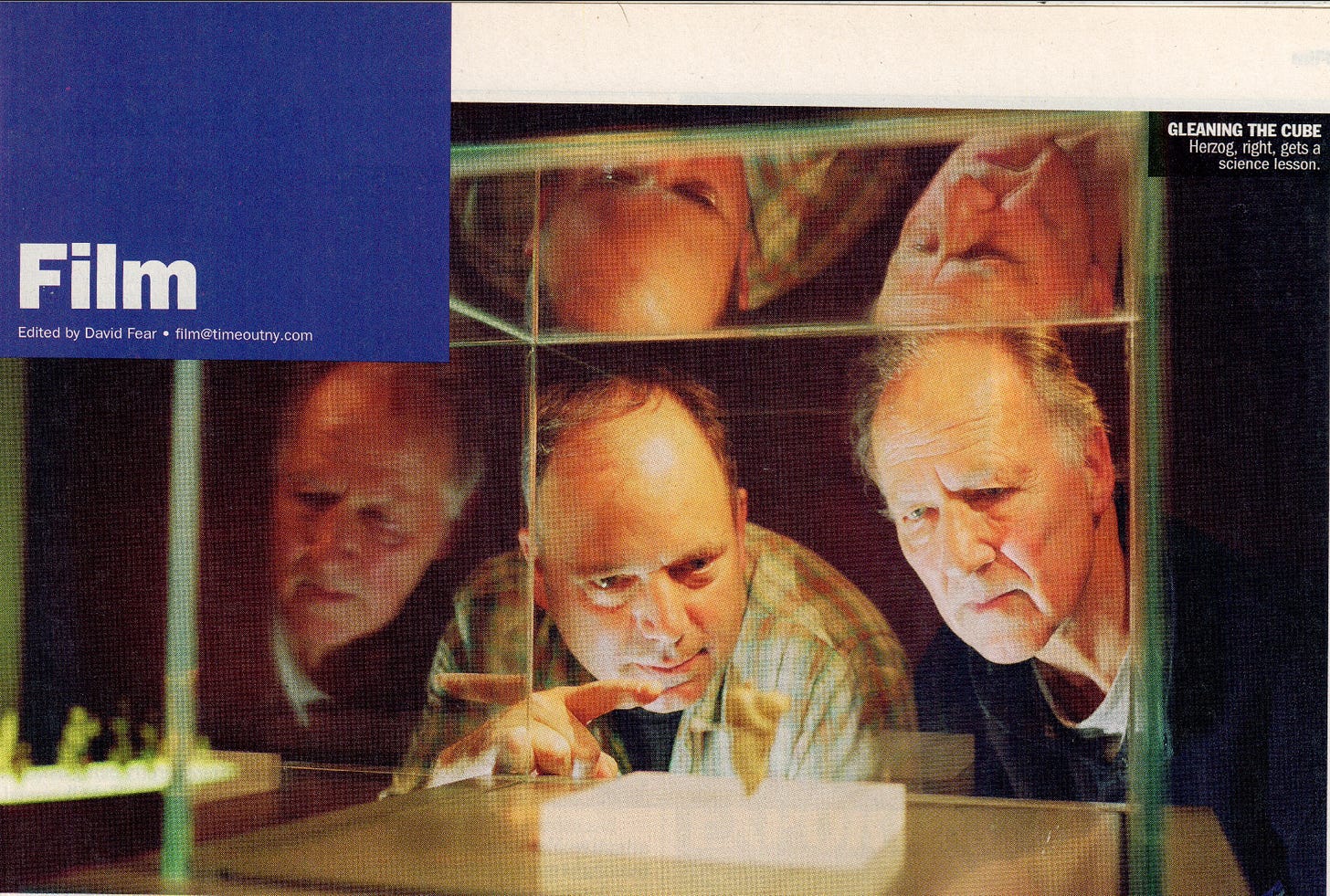

Several decades later, the child — now a grown man whom cinephiles and Simpsons fans know as Werner Herzog — was approached by his producing partner, Erik Nelson. “Erik came to me and wondered if I would be interested in making a documentary about Chauvet Cave in southern France,” the director, 68, says while sitting in a Manhattan hotel suite. “It instantly brought up that memory of me as a boy so deeply fascinated by a book about cave paintings, and how the discovery of that book awoke something in me so many years ago — a newfound independence. So of course, I told Erik that I’d drop everything and start work immediately.”

The result, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, follows Herzog as he descends inside the ancient Chauvet and explores its abundant 30,000-year-old visual treasures. Discovered in 1994 by speleologist Jean-Marie Chauvet and his team, this monolithic testament to mankind’s past houses elaborate drawings of horses, bison and mammoths, as well as glittering stalagmites and stalactites. There are even remnant of extinct species, everything preserved as if time has stood still. Given his boundary-pushing features like the Antarctica-set Encounters at the End of the World, it’s hardly surprising that Herzog was the first filmmaker granted permission to enter Chauvet. Armed with a small crew and some modified 3-D cameras, the director photographed as much of the cave as possible, and emerged with a striking stereoscopic record of a site few will ever see in person.

But since the cave’s fragile interior needs to be maintained at all costs, the work came with a number of limitations. “The restrictions were very severe,” Herzog says. “Very short time. Very few people. Very small amount of equipment. You’re not allowed to step off of the metal walkway the scientists have installed, nor can you sneeze. If you sneeze, you will destroy evidence. And God forbid if you had forgotten to take a leak in the morning. The only entrance and exit to the cave would be opened, but that would be the end of the shooting day. As a filmmaker you have to live with these things. You better live with them, and have the best of the best with you.”

At Herzog’s side was his longtime cinematographer, Peter Zeitlinger, 50. (“You throw anything at him, he’s going to deal with it,” the director proudly notes.) Reached by e-mail while shooting on location, Zeitlinger seconds his collaborator’s play-the-hand-you’ve been dealt approach to moviemaking. “To use obstacles and restrictions to your advantage is one of the basics of creativity,” he says. “If there are none, you have to create some. On Cave, there were enough difficulties to keep us all focused. The production company originally tasked us with creating a glossy, clean look. But we realized very quickly that this was impossible, so we improvised some software and assembled two tiny semiprofessional 3-D cameras that we stabilized with a gyro to photograph the cave interior. The 3-D is a necessity. There is no other way to show how these ancient artists expressed their perceptions.”

Herzog is similarly adamant about the need for the added visual dimension. “I’m a mild skeptic of 3-D,” he says. “But from the first moment I saw the cave it was too obvious. The formations are completely wild with bulges and pendants and niches — all of them utilized by the painters of that time. Plus, it’s probably the only film that will ever come out of this cave. It was absolutely imperative to shoot in 3-D..”

Despite the ongoing arguments over stereoscopic imagery (corporatized fad with a limited lifespan or progressive tool with still-unexploited potential?), Herzog fondly remarks that most audience are enthralled with this particular use of the technology. “I have attended several screenings of Cave,” he says. “The beauty of them all is that, as the crowds are leaving the theater, no one talks as if they have just seen a motion picture. They all speak as if they have been in the cave itself. The audience doesn’t even notice they are watching a movie. As a filmmaker, I think this is one of the best things you can do.”