Back to normal…

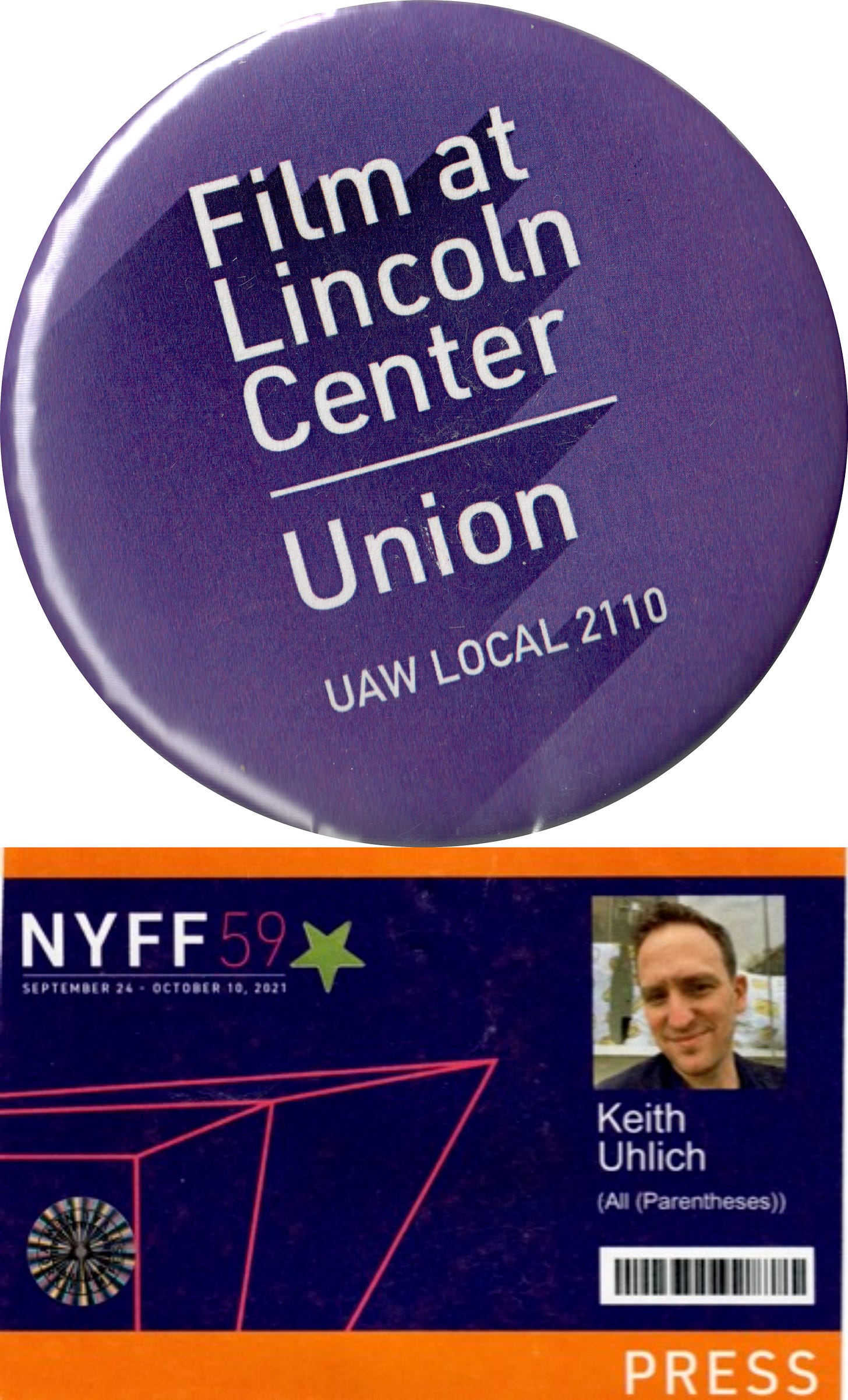

Masks and vaccination status (designated by a gold star affixed to your press badge) and some first day anxieties notwithstanding, the 59th New York Film Festival felt like business as usual. Though this was the year — my 19th accredited — that I attended the most screenings, so I clearly had a not-quite-post-COVID hunger for the vaunted “theatrical experience.” It was nice to be back in a crowd, even one mostly comprised of eyes and the occasionally defiant exposed nose and mouth. (Rex Reed, you rabble-rouser! Michael Musto, you mutineer!) Also business as usual: The evident divide between Film at Lincoln Center’s front-of-the-house workers and those corporate higher-ups who attempted to distract from the former’s collective bargaining efforts (for better pay and health insurance) with Magic Of The Movies™ blather and hollow hey-you-up-in-the-projection-booth! shoutouts. As of this writing, a deal still hasn’t been reached and, for the powers-that-be, “we’re still in discussions” stalling is the order of the day. Meet the new boss/Same as it ever was, to mix pop libretti.

I waited longer than I should have to ask for a button showing solidarity with the unionizers, mainly due to a paralyzing sense of poseurishness. If one isn’t directly involved with the struggle, do expressions of concord from the sidelines matter? That was the parley in my head, anyway. An argument exacerbated by similar ones I gathered were playing out on Twitter and Facebook, from which I’ve near-fully extricated myself, and which I recommend the rest of you take steps to do as well since Jack Dorsey and Mark Zuckerberg’s tech-bro Skinner boxes are cesspools of meager short-term merits and few-to-zilch enduring benefits. As for the FLC union, best head over to their website and follow their leads…which include posting on social media and showing concord from the sidelines. Fear is the mind killer, cynicism the soul-sapper. Keep pushing back, however you can.

To the mo-pics: I caught a pre-festival screening of Titane, Cannes top-prizewinner and all-around piece of shit. Nice to get the worst out of the way, as well as to satiate my inner grump (“To this they give the Palme d’Or?!?,” he sighed, head in hand). I sensed something was off from an early, shakily-executed tracking shot following automobile-obsessed exotic dancer/serial killer Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) around a sleazy vehicular Comic-Con. The point is to introduce her “point” — a BDSM-looking hairpin that Alexia wields during her kills. The visual foreshadowing is so obvious that it nullifies the sequence’s intended deadly-spell enchantment. You know when you’re in the hands of a con artist as opposed to a magician, and based on Titane, director Julia Ducournau is resoundingly the former. Admittedly, I cringed when she wanted me to (particularly during a gruesome, porcelain-sink-assisted face remolding), while gawping at the central sexual transgression between horned-up woman and sentient muscle car. But visceral reaction is not endorsement.

I responded semi-favorably to the virile mawkishness of Vincent Lindon’s character, a steroid-addicted firefighter mourning the loss of a child whom Alexia channels in ways that pander to the gender studies wings of ivory-tower academe as well as the Dub-you Dub-you Dub-you content click farm. But that was mainly due to my Proustian madeleine-esque recollection of Lindon’s grief-suffused performance in Claire Denis’ Bastards, of which his work here is a cartoonish degradation. Titane consistently does worse what’s been done better elsewhere; the Cronenberg parallels have been copiously noted, though the film’s provocations rarely rise to the schoolyard-japing level of Ken Russell. (Tom Six’s derriere-devouring oeuvre is more this shameless movie’s speed.) A scene in which a group of sweaty, shirtless firemen rave out in front of the French flag, followed soon after by Alexia’s contrastingly gender-queer gyrations, suggests a half-assed political statement of some sort, as does the moronically mecha-celestial finale: Long live the new-but-old-but-retread flesh?

Paul Verhoeven, at least, is a provocateur with pedigree, though I’ve never personally fallen for much beyond Robocop, as even in his best work, his baser instincts tend to leave a sour taste (the rape scene in Showgirls being the preeminent example of a sorry-I-just-can’t crossed line). I’m not head-over for his latest, Benedetta, though it’s the most consistently engaged and entertained I’ve been by a Verhoeven film in a long time. Sentiment has something to do with it — finally Paul gets to make his long-dreamed-of Jesus movie. Though the son of the Almighty only appears in lovingly lurid dream sequences as a kind of stigmata-afflicted Fabio, an object of lust for ecclesiastically-aroused 17th-century nun Benedetta Carlini (Virginie Efira).

Benedetta’s visions are legion, from the sacred to the profane, but nothing quite tops the erotic charge of her getting-to-know-you colloquy with cheeky novitiate Bartolomea (Daphne Patakia) while they drop mutual deuces. Shart is sexy, and Benedetta’s horndog piety is a threat to the convent’s old school abbess (Charlotte Rampling), convinced this self-assertive up-and-comer is faking her ecstatic reveries. The craziness escalates to the point of libertine lesbianism, suicide under a blood moon, a roiling plague, and a late appearance by Lambert Wilson as a “burn her at the stake!” nuncio. Best in Blasphemous Show is the dildo whittled out of a Virgin Mary statue. But what’ll linger for me is the gratified smile on Rampling’s face right before she calmly strolls into a blazing pyre.

Films about filmmaking are a personal kryptonite, though I was won over by Mia Hansen-Løve’s Bergman Island, with its über-subtle shifts between reality and fantasy. As in M. Night Shyamalan’s beguilingly asinine Old, Vicky Krieps is the grounding force, so perfect here as Chris, one-half of a motion-picture-making couple (Tim Roth’s Tony being her serenely supercilious other) on a pilgrimage to Ingmar Bergman’s island home of Fårö. They clash in their way like the seaside scenery does with the isle’s touristy vibe. Par for the course with Hansen-Løve, there’s no extreme of behavior that she can't subdue into deceptively anti-dramatic stasis, even with the arrival of a second couple, Amy (Mia Wasikowska) and Joseph (Anders Danielsen Lie), who alternate between hall-of-mirror figments of Chris’s imagination and fleshly real-world vessels for her creative drive. Even at its most heated, the interpersonal drama barely reaches a simmer. That the film still manages to attain vast levels of emotional resonance speaks to Hansen-Løve’s talent for mining her characters’ quiet lives for all they’re worth.

The bookending scenes of Maureen Fazendeiro and Miguel Gomes’s The Tsugua Diaries are sheer bliss, as two groups of people (a small one at the start, a larger one at the finish — though “beginning” and “ending” are inverse concepts here) rock out to Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons’ “The Night.” What comes between is, unfortunately, the kind of irritating movie-about-moviemaking comprised more of artistic referents than lived experience. Initially, there are three characters (played by Crista Alfaiate, Carloto Cotta and João Nunes Monteiro), whiling away the summer as roommates and romantic rivals. Fazendeiro and Gomes’s conceit is that the story is told backwards (Tsugua being “August,” you see). So the amorous release that might typically be built to comes up front, then about-faces. Additionally, as the tale progresses, a greenhouse the trio is erecting gets further and further dismantled.

Eventually, it becomes clear that The Tsugua Diaries is taking place during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (oh goody, one of those). And about midway through, after several other people (Fazendeiro and Gomes included) appear with little explanation or acknowledgment, it’s revealed that we’ve been watching a film within the film, and now will be privy to a backward-advancing look at that movie’s (un)making. As with Gomes’ Tabu, which riffed on F.W. Murnau, inspirations overwhelm ingenuity and insight. There’s nothing in the torturously meta-cinematic approach here that wasn't done better in Fassbinder’s Beware of a Holy Whore or Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees. Though my own personal pet peeve is the way Mário Castanheira’s grain-speckled celluloid cinematography mimics Néstor Almendros’ effortlessly naturalistic work on Eric Rohmer’s Pauline at the Beach without once — outside of those opening and closing exceptions — reaching a similar level of sublimity.

I’m more forgiving of the meta-cinematic elements of Aleksandre Koberidze’s What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? since they’re wedded to a euphoric fairy-tale notion — prospective lovers unable to recognize each other except through the projected image — though the film takes its tediously sweet time getting there. Lisa (Oliko Barbakadze) and Giorgi (Giorgi Ambroladze) meet twice by chance in the Georgian city of Kutaisi (the pair’s first encounter is evocatively framed from the knees down; their second from a telescopic distance), but then have their first official date upended when they awake in different bodies (Ani Karseladze and Giorgi Bochorishvili play the “reborn” duo). Knowing the location (a waterside café) where they were to meet, they stake out the area, take odd jobs, and eventually, as the memory of their aspiring romance fades, settle into the leisurely, unpredictable rhythms of life. The forgetting, or at least a certain haziness of mind, is the point, and Koberidze, who also narrates on occasion, complements this sensation by wandering off on multiple magical-realist tangents. I was charmed by the two dogs that frequent different outdoor restaurants depending on which World Cup match is screening, and one section focusing on a soccer ball kicked around in slo-mo before being lost to the raging Rioni River attains a poetic/political melancholy that is very moving. Yet there’s an overall wobbliness to most of the meanderings, as if Koberidze is too besotted with the conceptual possibilities of his digressions, and so fails to hone them into something truly special.

I wrote about NYFF's opening night selection for Slant, though I'll reiterate here that Joel Coen’s adaptation of the Scottish play (what, Macbeth? “Ahhhh!!! Hot Potato, orchestra stalls, Puck will make amends!”) is best in its peripheral details. The Tragedy of Macbeth has my favorite-ever incarnation of the three witches, all played by Kathryn Hunter, and a hilarious one-and-done appearance by Stephen Root as the drunken Porter. No surprise that Coen, working for the first time sans brother Ethan, can so effortlessly bring the margins of a movie to life. And yet he fails to wrangle much memorable from his two leads, Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, as the scheming Lord and Lady whose murderous machinations bring them innumerable damn'd spots. They’re just kind of there, vacantly bellowing to and from the void. I’ve frequently been lukewarm on Coen movies on first view, only to about-face when I find myself quoting them incessantly. There’s something unquantifiable about their dialogue and how it takes up residence in your being. (A line like “Mr. Treehorn treats objects like women, man!” might eventually attain the power of a Zen koan, transcending one’s busted gut.) I can’t see something similar happening here given the clear disconnect between Shakespeare’s inimitable iambs and Coen’s aesthetic approach, a faux-Wellesian embalming of the material with disparate elements (Bruno Delbonnel’s luxuriant black-and-white cinematography; Stefan Dechant’s spare, suggestive production design) that are impressive on their own, yet which never quite cohere.

Michelangelo Frammartino’s previous feature, Le quattro volte (2010), struck me as too schematic, its “gorgeous” imagery shotgun-married to an interconnected man/animal/plant/mineral quartet of tales that pensively strained for philosophical grandeur. By contrast, his eleven-years-later followup, Il buco, is a superb meld of sound, image and ruminative essence. The film interweaves two threads: A dramatic re-enactment of the real-life exploits of the Piedmont Speleological Group — who in 1961 mapped an uncharted cave in the south of Italy — and the simultaneous slow demise of an elderly shepherd (Antonio Lanza) who, it’s implied, has long watched over the land where the entrance to the cave is located. No need for qualifying quotation marks, since the gorgeous visuals here, beginning with a stunner in which a herd of cattle peer over the edges of the cave’s chasmic ingress, are perfectly in tune with the larger themes being explored. (Cinematographer Renato Berta has collaborated with everyone from Straub-Huillet to Godard, from de Oliveira to Garrel, and this is among his very best work.) The further the spelunkers make their way into the alternately vast and claustrophobic caverns, the closer the shepherd comes to death; it’s as if his body and the hollows of the earth are connected in enigmatic ways that the explorers are unwittingly out to literalize. (One telling shot graphic-matches a spelunker’s flashlight beaming down from a high-above ridge with a physician’s penlight as it illuminates the shepherd’s non-responsive pupils.) At heart this is a story about the price of progress, though I don’t think Frammartino is taking a regressively hard stance against scientific or sociocultural advancements. Il buco is less manifesto than inquiry, building to an elliptical finale that suggests the things we lose corporeally still echo — across outer and inner worlds — for eons.