The Aussie director takes us on another extreme adventure in The Way Back.

A group of people wanders through the Gobi desert. The sun is beating down; the horizon, in all directions, seems infinite. Waves of heat rise in sinuous patterns, further blurring the perspective. Mirages are a given: Is that an oasis in the distance or just an elemental tease?

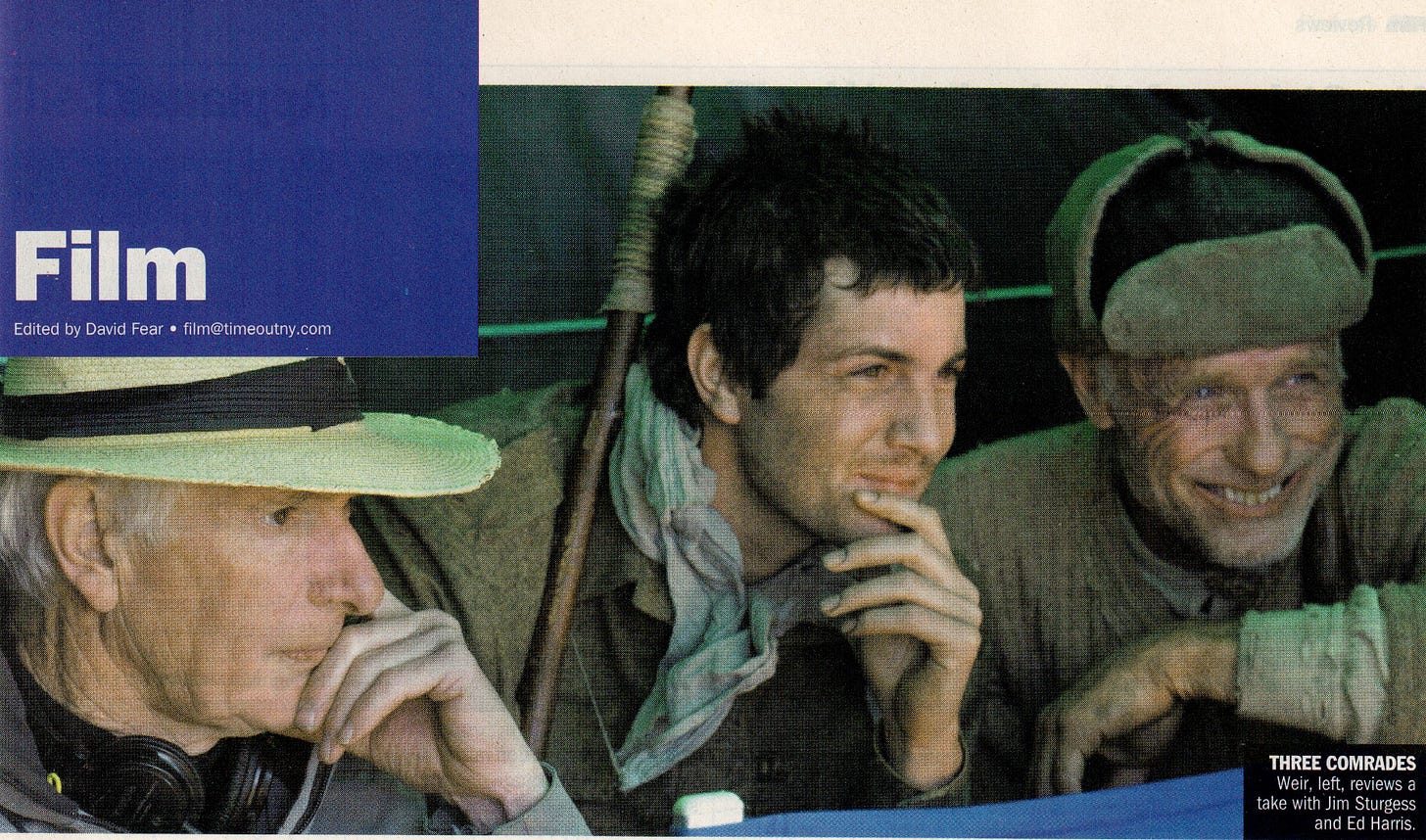

This striking sequence comes midway through The Way Back, Australian filmmaker Peter Weir’s steadfast and unflinching account of World War II Siberian gulag escapees, which the cowriter-director adapted from Slavomir Rawicz’s book The Long Walk: The True Story of a Trek to Freedom. Though the film features a wide swath of terrains — arid flatlands, labyrinthine forests, snowy mountains — the fugitives’ extended hike through the vast Mongolian sand dunes has earned it numerous comparisons to Lawrence of Arabia. But sitting in a midtown office, Weir, 66, is quick to demur.

“I think that comparison is just because of the desert,” he says with a gracious smile. “For me, the only film influence was Akira Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala, which was actually shot in Siberia. The way in which very little happened in terms of incident or confrontation in that movie held me so strongly as a viewer. Cinema is particularly suited to disturbing your equilibrium, stimulating you to see the world afresh. As a filmmaker, I search for subjects that have some kind of invisible connection with my own sensibility. The Way Back appealed to that mysterious part of myself that is not going to dance to anybody’s tune.”

Weir has been forging his own path for years. One of the leading lights of the Australian New Wave, alongside such talents as Fred Schepisi (The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith) and George Miller (Mad Max), he built his reputation on art-house head-scratchers like Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and The Last Wave (1977). (“I was lucky to have been there,” he says of the influential cinema movement. “Right place. Right time.”) Historical spectacles (1981’s Gallipoli) and plum Hollywood assignments (1985’s Witness) followed. Yet even the most crowd-pleasing of the director’s films, like the Robin Williams boarding-school drama, Dead Poets Society (1989), have intriguingly off-kilter sequences — Robert Sean Leonard’s haunting, near-pagan suicide — that could only come from Weir’s purview.

Sweeping in look and intimate in scope, The Way Back fits comfortably into the filmmaker’s eclectic oeuvre. Its cast is a cosmopolitan grab bag: American (Ed Harris), British (Jim Sturgess), even several leading lights of the Romanian New Wave (Alexandru Potocean, Dragos Bucur). And the drama, as in Weir pictures like The Mosquito Coast (1986) and Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), stems more from the escapees’ interaction with the landscape than with each other. Nature is the silent antagonist (“our prison,” one of the characters observes, and in contrast with the current cinema’s digital-heavy tendencies, Weir mostly took his cast and crew to actual, potentially unforgiving locations.

“I went to the real places, then recast them with other countries,” he says. “The Bulgarian forest became the Siberian forest. Morocco was Gobi. I find that method very inspiring, though you can fall into a dangerous trap. Since it’s such an adventure to get out to these places, you can easily think that will come across on film. Sometimes you look at your dailies and it’s quite a shock. Fortunately, here it was extremely evocative.”

Sturgess, 32, heads the ensemble as Polish refugee Janusz, who desperately wants to be reunited with his wife. Speaking by phone from Los Angeles, the actor expressed deep admiration for his director’s methods. “With Peter, everything is so detailed — it must be correct and truthful,” he says. “He really searched far and wide for those locations. Same with the languages: A lot of films have people speaking only accented English. But he made the decision to have English be only the collective language. When a character was speaking to someone from their own country it would be in their native tongue. Again, it’s just Peter trying to find the truth in it. I felt so taken care of. When you act in an environment like this, all you need to do is exist.”

That existence, at least onscreen, is a harsh one. As the fugitives journey through the varied punishing terrains, they are scarred physically (bloody, blistered feet are a constant) and emotionally (one character is so overcome by subzero temperatures that he wanders off in a hallucinatory fervor). Yet their goal remains simple: survive. The same might apply to distinctive moviemakers. Put the question to Weir — whose films are increasingly far between — as to how he maintains his unique perspective in today’s cinema, and he replies with an acquiescent, yet still optimistic tone. “I’m finding it harder, certainly,” he says. “The market is now primarily for children or the films are childish. I could always get out if I wanted to. But in a way, filmmakers never retire. I think you just have to adapt. And adapting in my case means not making films that I don’t feel for. I just can’t do it.”