The Adventures of Tintin

Time Out New York Project: Issue #841, December 15-28, 2011

★★★★☆

Dir. Steven Spielberg. 2011. PG. 107mins. Jamie Bell, Andy Serkis, Daniel Craig.

Print Version

Steven Spielberg’s breathlessly entertaining 3-D motion-capture animated adventure about the intrepid boy reporter with the distinctively pointy hair quiff has long been in the making. (The comic’s creator himself, Hergé, reportedly said that only the helmer of the globe-hopping Indiana Jones movies could do justice to his work.) Spielberg surely understood that his Tintin had to set itself apart from its source, so the filmmaker tips his hat in the opening scene (Hergé appears as a flea-market caricaturist) and then defaults to set-piece-heavy spectacle mode — all surface, but what surface! The script, a clever mishmash of three separate Tintin adventures (The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Secret of the Unicorn, Red Rackham’s Treasure), follows our dauntless hero (Bell) as he searches for buried loot.

Two others have a stake in the fortune: villainous Ivan Ivanovich Sakharine (Craig) and Tintin’s confidant, drunken sea captain Archibald Haddock (Serkis). Serkis is Hollywood’s go-to motion-capture performer for a reason, finding pathos in Haddock’s head-conking pratfalls, while Bell’s Tintin is all involuntary, idealistic and infectious curiosity. As for Spielberg himself, the father of the modern blockbuster swoops and soars here with an unfettered freedom that’s exhilarating. (If the concurrently released War Horse is the director’s Charlie Chaplin–esque tearjerker, then Tintin is his eyes-agog Buster Keaton comedy.) And the film’s open-ended finale feels just right, less a sequel-ready concession than a celebration of Hergé’s sui generis creation: For Tintin and friends, the adventure is always ongoing.—Keith Uhlich

Extended Online Version

“Everybody knows him. That’s Tintin.” So says a peripheral character at the start of Steven Spielberg’s breathlessly entertaining 3-D motion-capture animated adventure. But if you’re U.S. born and bred, it’s most likely you've never heard of the intrepid boy reporter with the ankle-baring plus fours, distinctively pointy hair quiff and ever-present canine companion. So a bit of background: The Adventures of Tintin was initially one of several ongoing comic stories created by the artist Georges Remi — pen name: Hergé — for the youth supplement of the Belgian conservative daily Le XXe Siècle. The strip’s popularity grew quickly during the ’30s and became a phenomenon in Europe over subsequent decades. (Hergé was working on the series’ 24th, ultimately unfinished adventure at the time of his death in 1983.)

Since then, Spielberg — who first read the books’ English translations in the early ’80s — has been linked with Tintin’s onscreen legacy to varying degrees. In a perhaps apocryphal story, Hergé reportedly said that only the helmer of the globe-hopping Indiana Jones movies could do justice to his work. Such high praise (and/or good promotional copy), though the long-gestating result does, for the most part, bear out the writer’s purported blessing. This lifelong Tintin fan was more than pleased, even while having to acknowledge that the movie lacks the subtle state-of-the-world commentary that Hergé often smuggled into his creation: Japan’s resignation from the League of Nations, civil unrest in South America, even the race to the moon were all ripped-from-the-zeitgeist plot points in the series, albeit ones that a movie blockbuster of the moment couldn’t hope to capture with the same pointedness.

But that’s a nitpick in the grand scheme. Spielberg surely understood that his Tintin had to set itself apart from its source, so he tips his hat to Hergé in the opening scene (the artist appears as a flea-market caricaturist) and then defaults to set-piece-heavy spectacle mode — all surface, but what surface! The script by Steven Moffat, Edgar Wright and Joe Cornish is a clever mishmash of three separate Tintin adventures (The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Secret of the Unicorn, Red Rackham’s Treasure) and follows our dauntless hero (Bell) as he searches for buried treasure. Two others have a stake in the fortune: Chief antagonist Ivan Ivanovich Sakharine (Craig), upgraded from a minor character in the comics to scarlet-garbed villain du jour, and drunken ship’s captain Archibald Haddock (Serkis), who becomes Tintin’s well-meaning yet defiantly imperfect confidant.

Serkis is Hollywood’s go-to motion-capture performer for a reason, and he finds the pathos in every one of Haddock’s bad decisions and head-conking pratfalls (he’s particularly extraordinary in the movie’s extended centerpiece, when the tipsy seaman recalls his ships-in-battle ancestry). Haddock is the tragicomic foil of the Tintin series; in contrast to the one-note buffoonery of police inspectors Thompson and Thomson (Simon Pegg and Nick Frost), who anchor the story’s pickpocket side plot, the character’s perpetually soused demeanor masks a world of inner hurt. Bell, meanwhile, is a wonderful Tintin — all involuntary, idealistic curiosity. Clues are to him like carrots are to Bugs Bunny, and his what’s-lurking-round-the-corner enthusiasm is, like the rest of the film, infectious.

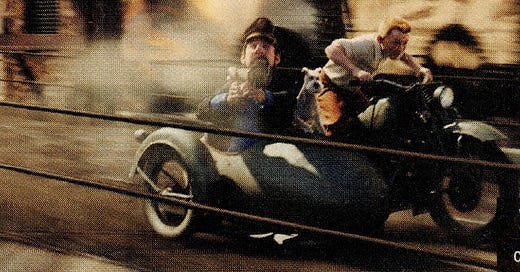

As for Spielberg himself, the father of the modern blockbuster is particularly energized: His camera has always been effortlessly mobile, but here it swoops and soars with an unfettered freedom, as in an astonishing incident-upon-incident motorcycle chase through a seaside Middle Eastern city. The effect is exhilarating. (If the concurrently released War Horse is the director’s Charlie Chaplin–esque tearjerker, then Tintin is his eyes-agog Buster Keaton comedy.) And the film’s open-ended finale feels just right, less of a sequel-ready concession than a celebration of one of the essential tenets of Hergé’s sui generis creation: For Tintin and his friends, the adventure is always ongoing.—Keith Uhlich