Tsai Ming-liang, Taiwan's art-house auteur

Time Out New York Project: Issue #737, November 12-18, 2009

Immerse yourself in the films of a master. By Keith Uhlich

The cinema of Malaysia-born, Taiwan-based director Tsai Ming-liang can be accurately described as an acquired taste. There’s no shame in limited appeal, though it’s always heartening for those of us who love this mostly festival-feted auteur’s work when a few more acolytes join the fold.

Asia Society’s retrospective “Faces of Tsai Ming-liang” is a welcome primer, but the grab-bag nature of the series is slightly disappointing, since Tsai’s films benefit from being seen in close-together chronology. The title of one unrepresented feature, The River (1997), is a perfect encapsulation of how his body of work operates, each entry hearkening back to an ever-receding source while flowing sinuously forward into unchartered waters.

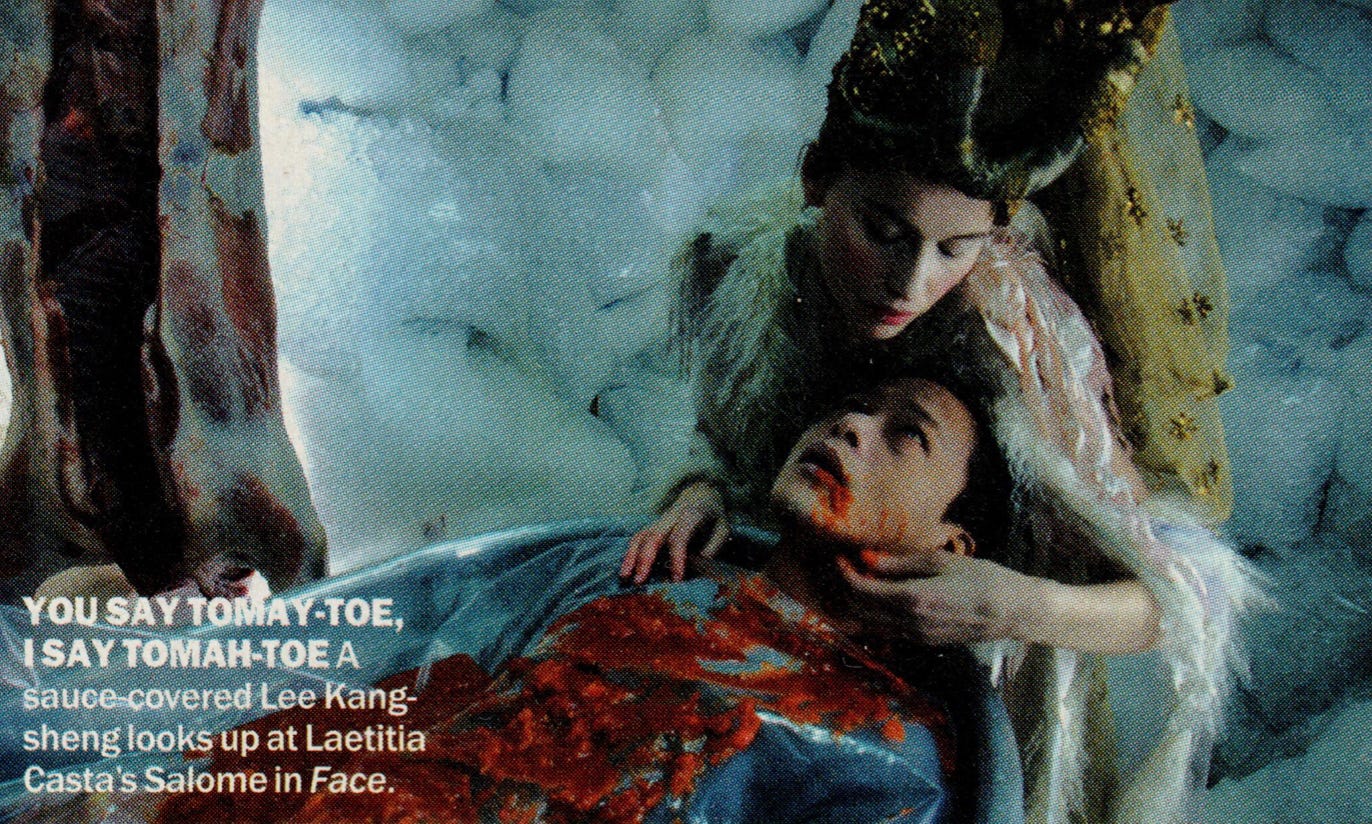

The one absolute is recurring protagonist Hsiao-Kang (Lee Kang-sheng), who has rightly been described as the Antoine Doinel to his creator’s François Truffaut. He’s a much more malleable presence than that nouvelle vague mainstay, though it’s always fun to try and tease out the connections between, say, the introverted, youthful Hsiao-Kang in Tsai’s first theatrical feature, Rebels of the Neon God, and the mournful, middle-aged one in the director’s most recent effort, Face (2009).

In Rebels, Hsiao-Kang is a reclusive teenager who stalks and torments a Taipei delinquent (Chen Chao-jung). By the standards of what follows, this is Tsai’s most conventional film. His trademark static-shot long-takes that are his stylistic hallmark are in their early, developmental stages and there are more traditionally employed musical cues throughout, though this probably guarantees an overall accessibility that subsequent titles aren’t likely to provide.

Vive L’Amour (1994) follows Hsiao-Kang, a street vendor (Chen Chao-jung again) and a real estate agent (Yang Kuei-Mei) as they move disaffectedly through the same vacant apartment, often ignorant of each other’s presence. It’s constructed like a revolving-door farce, though Tsai’s sense of humor tends toward gruelingly deadpan displays, making the laughter stick in our throats.

The same goes for The Hole (1998) and What Time is it There? (2001), which should not be missed, since both set the stage (the former through out-of-nowhere musical numbers; the latter via the grief-stricken dual-locale narrative) for the masterful Face. It’s tempting to call Tsai’s latest—in which Hsiao-Kang directs a Louvre-set adaptation of the myth of Salome—his crowning achievement. The presence of Fanny Ardant and Antoine Doinel himself, Jean-Pierre Léaud, brings the director’s Francophile obsessions to the fore, though it must be acknowledged that the constant callbacks to his previous films will probably baffle and aggravate newcomers (walkouts at Cannes were reportedly legion). A scene in which Hsiao-Kang wades hesitantly through an underground aqueduct approximates the ways in which viewers must willingly immerse themselves in Tsai’s singular worldview. The hope, as the end of sequence implies, is that you’ll eventually hear the music.