"Who Wants to Die for Art!?!": Reflections on a Meta-Film Sub-Genre: Introduction

𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘚𝘲𝘶𝘢𝘳𝘦

“A work of art should be like a well-planned crime.”

—Charles Baudelaire“Tragedy on the stage is no longer enough for me — I shall bring it into my own life.”

—Antonin Artaud

In a pivotal scene from Ruben Östlund’s The Square (2017), a performance artist, Oleg (Terry Notary), imitates with uncanny physical prowess the movements and behavior of a ferocious ape. His act is staged at a lavish gala for some of Sweden’s wealthiest citizens, donors to a prestigious art museum, the X-Royal, that is hosting the event to showcase its cutting-edge work. At first, Oleg's performance causes the dinner attendees to become noticeably tense. After a public address announcement warns that a wild animal will soon be unleashed in the room, and that any signs of fear or aggression will be met by this animal with violent reprisal, the patrons all assume postures of stiff, silent anxiety.

Hulking, shirtless, and completely believable as a simian, Oleg enters the ballroom, stalking the attendees with bestial intensity and menacing suspicion. On occasion he defuses the charged atmosphere with humorous, apelike responses: a burst of childish laughter, a napkin placed daintily on a man’s head. But the performance takes a terrifying turn when Oleg uses his intimidating bulk, as well as a series of guttural cries, to taunt a patron out of the room, and then — after the museum’s chief curator (Claes Bang) fails to bring the event to a close — nearly rapes a female attendee. She is rescued at the last moment by several tuxedo-clad multi-millionaires who overpower the artist as they scream, “Kill him!”

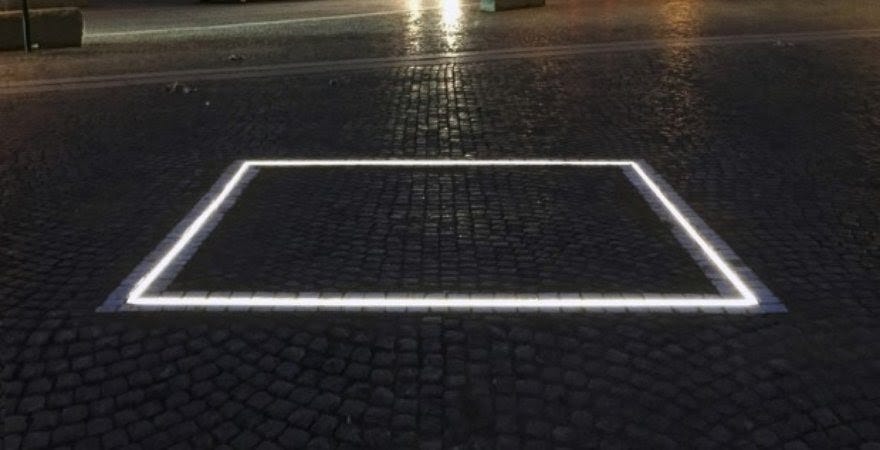

On one level, this sequence lampoons instances in which a performance artist “went too far.” Indeed, the scene specifically spoofs real-life artist Oleg Kulik, who once acted like a dog and ended up not only biting a museum visitor, but also destroying some of the institution’s valuables. In this sense, The Square makes the fairly obvious point — as have so many other art-world satires (Art School Confidential [2006]; (Untitled) [2009]; sundry Woody Allen films) — that post-modern art has become so extreme in its provocations as to move beyond intentional agitation into outright despicability. But on another level, The Square foregrounds a dilemma at the core of artistic practice as a whole: as moving and influential as it can be, art too often exists in a realm separated from “real life,” cordoned off as safely “consumable” entertainment in opposition to the rest of our unpredictable — and often dangerous — existence. The performance art sequence from The Square thus epitomizes its major theme: the disparity between art’s ennobling aims — as represented by the fictional artwork from which the film draws its title, an outdoor installation that encourages museum-goers to reconnect with their common humanity as members of a civilized society — and the recalcitrant nature of an oft-chaotic, oft-nihilistic world that seems to remain untouched, and unchanged, by that art.

With all this in mind, we can see the goal of The Square’s performance artist — as we can the goal of many real-life performance artists — as demolishing the barrier between art and reality. The ape-man’s method for doing so, however, transgresses not just the conventions of entertainment, but also the rights of others. It thus enters into the realm of criminality, an arena where art can no longer justify the artist’s goals. Of course, throughout history artists have tested the limits of written and unwritten law in order to move art further into forbidden territory, to a place where audiences can no longer dismiss art as “make-believe” and must instead confront it as “incite-action,” as intensely and irrevocably Real.

Yet testing the limitations of infantilizing censorship is one thing, committing outright violations of personal and public security quite another. The Square asks whether contemporary art — its effects so often sterilized through the official patronage of institutions like the X-Royal — can only enact the most horrendous of deeds in order to break, as Kafka once put it, “the frozen sea inside us.” And if so, at what price? “The Square” of The Square intends to foster community (its motto: “‘The Square’ is a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it we all share equal rights and obligations”), but clearly doesn’t succeed in doing so. By contrast, the ape-man’s performance proves successful, but only through endangering several of its unwitting participants and stoking the basest impulses of others. Can the destruction of the art-life boundary only lead to our own destruction, plain and simple?

Further muddying The Square’s complicated inquiry is the fact that its performance art sequence is purely fictional and not a real-life document. Since Oleg’s actions and the gala attendees’ reactions were all staged by Östlund, the only potentially violated and outraged viewers of the performance are viewers of The Square. Does this dampen the effect of the performance? Notary’s portrayal of the ape-man is palpably disturbing, as is the sequence as a whole in its slow-burning dread and anti-social catharsis. But Notary’s performance and the sequence in which it takes place nonetheless exist at removes, as mise en abymes of reality-invading art, not as real McCoys. They are to be watched and experienced and mulled over in the comfort of a theater or living room.

Or are they? Perhaps The Square’s fictional scenario reverberates so strongly that it does break that frozen sea inside us, evoking — if not invoking — the contradictions of life (e.g., our civilized veneers versus our primitive urges) that we so profoundly struggle to harmonize and reconcile. Perhaps because it exists solely as cinema, the ape-man’s performance can take on another layer of disturbance, since the viewers of The Square can safely and vicariously experience a work of art that is not meant to be experienced safely and vicariously. We are implicated as the kind of spectator-consumers that the ape-man wishes to unsettle and unmask, and we are made aware of our latent hypocrisy in enjoying, or extricating ourselves from, the unsettling and unmasking of our fictional counterparts.

The Square is a recent instance of a singular type of motion picture — the meta-film in which an artist gravitates toward madness and/or criminality in an attempt to transcend the unsatisfying limits of representation and discover/uncover the Real. Of all such meta-films — films about films, or films about art — this sub-genre is the one that, like the ape-man sequence of The Square, most profoundly and disturbingly probes into art’s dichotomous roles within human culture: as reflection and creation, as mirror and tool, as product and expression, as contrivance and outgrowth of nature. Cinema studies professor Dana B. Polan has defined these dichotomies as the basis of self-reflexive art, which, he argues, merely makes explicit the latent tensions within all works of cultural production:

“Art, all art, bases itself not just on confirmation but also on contradiction. Literary critic Frank Kermode has alternatively described this interplay as one between credulity and skepticism…or between recognition and deception…. To a large extent, what we refer to as self-reflexivity represents one more strategy in the interplay of a technique intrinsic to and actually defining the process of art. One sort of pleasure comes from precisely this interplay of credulity and skepticism…. Self-reflexive art appeals in part because it heightens this intrinsic interplay.”

Yet the “artist-as-madman and/or criminal” film also provocatively amplifies the self-reflexive film’s already heightened “intrinsic interplay” (between viewer immersion and estrangement) due to its intense suspicion of art as a sufficient sociopolitical vehicle of expression, or at least as some kind of pinnacle of human cultural achievement. These films not only question the overvalued role of art in society, but also the ways in which life can be imbued with an artistry of its own, the kind that circumvents drudgery and routine so that existence itself becomes a “happening” in the control of a playful individual-turned-creator.

Since the protagonists of these films are often frustrated artists, their playful creativity frequently turns into a vengeful rage against a world that can’t appreciate either art or life. These protagonists often go insane, or, more often, commit atrocities, particularly within the psychological thriller or horror genres. Think Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Color Me Blood Red (1965), Elio Petri’s A Quiet Place in the Country (1968), Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer (1979), or Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). But these struggles with sanity appear in other guises as well, for example in the artist biopic (Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life [1956]), in the historical costume drama (Federico Fellini’s Satyricon [1969]), or in the dark comedy (Alan Arkin’s Little Murders [1971]).

No matter the genre cloak, this kind of meta-film consistently asks its viewers to meditate on the ultimate purposes of art. Why are artists driven to create? Why are audiences driven to consume art? And why are both parties so often disappointed with the results of art as it exists and functions in society? Sometimes this disappointment arrives when the artist falls short of an aesthetic ideal or standard. But more often, disappointment arises from the very act of creation, since creation can never quite assume the mantle of the Real.

In the twelve-part series that follows, I will attempt to trace the themes laid out above across several films from a wide array of time-periods, genres, and national cinemas. Part I is an analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), a work that explores the convergence of art, crime, transcendence, and self-incrimination, as well as the disturbing philosophical and moral implications of this convergence, an artist-as-killer film that makes for an exemplary study in the artist-as-criminal sub-genre’s meta-cinematic possibilities.

Works Cited

Polan, Dana B., “Brecht and the Politics of Self-Reflexive Cinema,” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, vol. 1, no. 1, 1974.