What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (1963) • It’s Not Just You, Murray! (1964) • Who’s That Knocking at My Door (1967) • The Big Shave (1967) • Street Scenes (1970) • Boxcar Bertha (1972) • Mean Streets (1973) • Italianamerican (1974) • Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) • Taxi Driver (1976) • New York, New York (1977) • The Last Waltz (1978) • American Boy: A Profile of - Steven Prince (1978) • Raging Bull (1980) • The King of Comedy (1982) • After Hours (1985) • Amazing Stories, “Mirror, Mirror” (1986) • The Color of Money (1986) • Michael Jackson: Bad (1987) • The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) • Location Production Footage: The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) • New York Stories, “Life Lessons” (1989) • Goodfellas (1990) • Made in Milan (1990) • Cape Fear (1991) • Armani, Eau pour Homme (1991) • The Age of Innocence (1993) • Casino (1995) • A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (1995) • Kundun (1997) • My Voyage to Italy (1999) • Bringing Out the Dead (1999) • The Neighborhood (2001) • Gangs of New York (2002) • The Blues: Feel Like Going Home (2003) • Lady by the Sea: The Statue of Liberty (2004) • The Aviator (2004) • No Direction Home: Bob Dylan (2005) • The Departed (2006) • The Key to Reserva (2007) • Shine a Light (2008) • Shutter Island (2010) • A Letter to Elia (2010) • Boardwalk Empire, “Boardwalk Empire” (2010) • Public Speaking (2010) • Bleu de Chanel (2010) • George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011) • Hugo (2011) • The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) • The 50 Year Argument (2014) • The Audition (2015) • Vinyl, “Pilot” (2016) • Silence (2016) • Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese (2019) • The Irishman (2019) • The Irishman: In Conversation (2019) • Pretend It’s a City (2021)

It took me until middle age to love Scorsese. He was so excessively marketed as a master in my teens and twenties that I rebelled with a puerile shrug and a bear hug for Goodfellas (always easy to adore). Now he seems a last bastion, certainly the most publicly film literate of the movie brat generation and, quality-wise, the most consistent. He’s fully formed from the first group of NYU shorts that crescendo to the agitprop Guignol of The Big Shave, a scathing depiction of a White world with blood on much more than its hands. And the callow scribblings of Who’s That Knocking at My Door (as spirited and self-assured as an anxiety-of-influence riff can get) and Boxcar Bertha (with its scrappy-doodle hippie Christian symbolism) would, for many other filmmakers, be apexes.

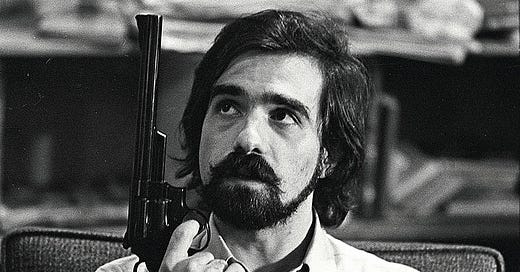

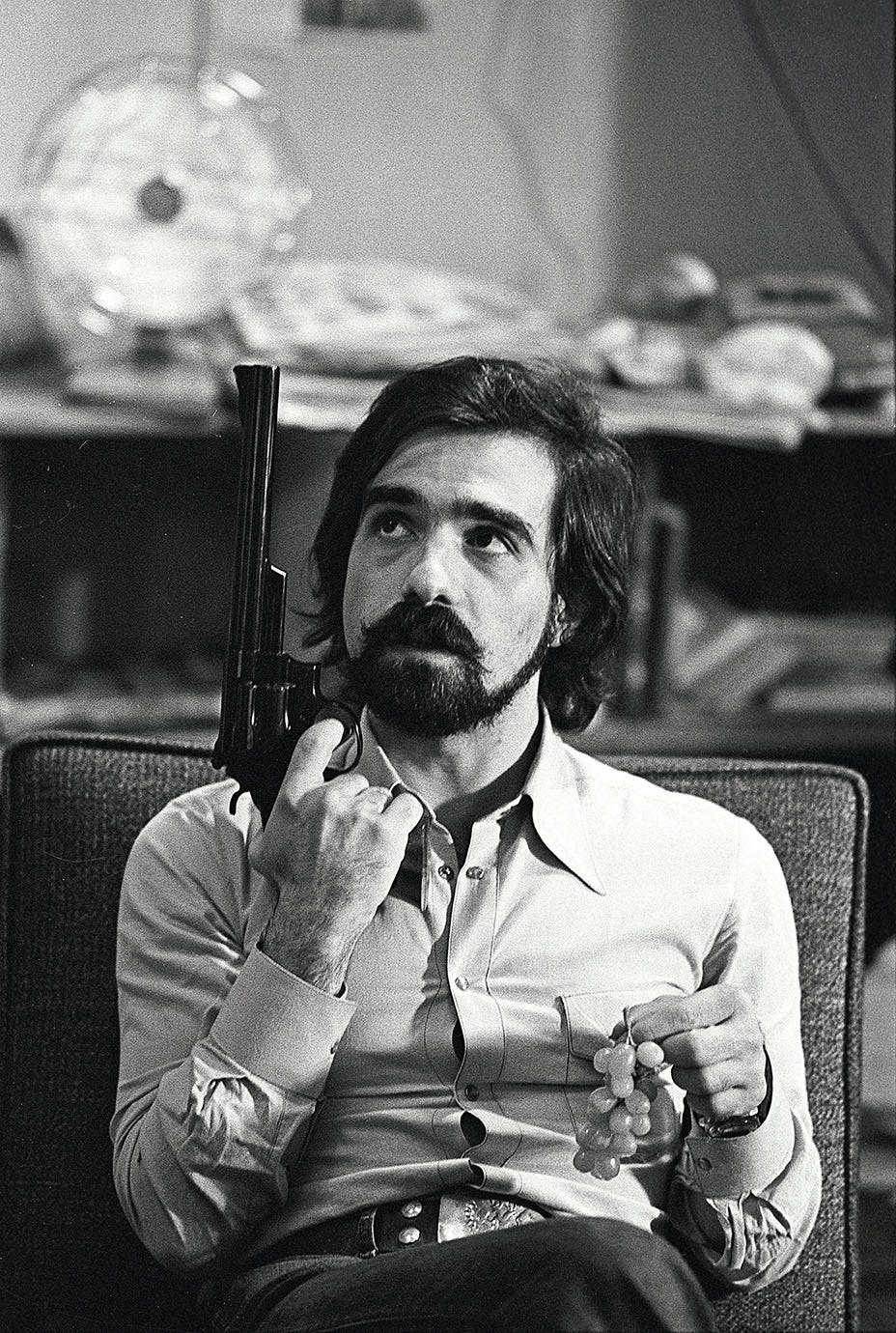

The run from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy is in some stratosphere all its own, with Robert De Niro on a parallel tightrope, unnervingly shape-shifting from Johnny Boy to Bickle to La Motta to Pupkin. I personally gravitate toward two of this stretch’s lesser-celebrated titles, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and New York, New York, because of the ways in which they futz with expectation (see the fantastical Old Hollywood musical opening of Alice) and how they foreground two resolute women, respectively Ellen Burstyn’s itinerant waitress and Liza Minnelli’s songbird-in-ascendance.

The world goes round and round and round: Scorsese is continually doxxed for his view of the ladies, his work being, at a glance, more interested in punch than Judy. And fair enough, considering the only two female characters who entirely cast off the bonds of Madonna-Whore-Shrew are Mama Scorsese and Fran Lebowitz, and that mainly due to their director’s familial/fannish deference. (Make it a trinity by adding his crucial off-screen professional partner, editor Thelma Schoonmaker.) This isn’t to rage-tweet that Anna Paquin needs more lines in the withering summative statement that is The Irishman. Her spectral pallor and bearing is plenty to get across that she has the moral high ground over De Niro’s Candide-ian grump of a mobster dad, sociopathically shambling his way through the worst of all possible worlds. And in case we miss the point, other daughter Marin Ireland gets to verbalize the unbridgeable nuclear abyss in her own powerful single-scene showcase.

Men may be more the focus in Scorsese’s frescoes, but it’s typically to emphasize their overcompensatory weaknesses, as with Nick Nolte’s obsessive large-canvas artiste Lionel Dobie in the “Life Lessons” segment of New York Stories. And all of his characters, regardless, tend to be united under the same shroud of chagrin. Suffering is the great theme; the notion is even defined by a monk in the A-for-effort Dalai Lama biopic Kundun. Doesn’t matter who you are: Henry Hill or Newland Archer, Hugo Cabret or Jesus of Nazareth, the latter, in the beguilingly jagged Biblical parable The Last Temptation of Christ, holding forth his beating heart in a graven image suffused with the deistic/demonic hues of Mario Bava. If you walk the Earth, you suffer. (Moonwalk in the case of Michael Jackson, star of Scorsese’s alternately absurd and impassioned music video for Bad.) And it’s the getting through — the long walk through the valley of the shadow of death — that’s most of interest to Marty.

The journey is rarely optimistic. Sin is just too damn enjoyable…until it isn’t. When a character gets their comeuppance, it’s minus any hint of judgment except, maybe, from on high. Yet if the filmmaking evokes God, it’s due to Scorsese’s reverence for the form in which he’s working, not because he’s certain that there’s something bigger than us out there. It’s our works, ultimately, that do us in. The bullet to the brainstem that fells Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) in Goodfellas hits as hard as it does because it comes from just below, not above. From this world, not the next. Pesci’s Nicky Santoro in Casino meets an arguably worse fate, his cockily omniscient voiceover cut off mid-sentence when turncoat associate Frank Marino (Frank Vincent) whacks him from behind with a baseball bat — the opening salvo in one of the Scorsese oeuvre’s grisliest dispatches.

Scorsese recognizes that each of us is capable of the worst. And that, given infinite chances at redemption, we’re more likely to reinvent ourselves, à la Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) in The Wolf of Wall Street, so we can foist our bad habits on other unsuspecting marks. There’s some truth to the received wisdom that DiCaprio is himself a hobbling addiction in Scorsese’s aughts endeavors. The fruitful, form-reinventing De Niro collaboration this isn’t, at least in the early going. Gangs of New York is more a showcase for Daniel Day-Lewis’s grandiloquent histrionics as Bill the Butcher, as well as exhibit A in Scorsese’s semi-acquiescence (outside of two keenly affectionate documentaries, A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies and My Voyage to Italy, about the films that shaped him) to the primarily Harvey Weinstein-superintended prestige market. This era culminated in an it’s-about-time! directing Oscar win for The Departed — a better movie than I initially gave it credit for, though more for its affecting allusions (Vera Farmiga and Matt Damon’s characters recreating The Third Man’s steely, speechless cemetery walk-by) than all the profanely Bahstan-accented cops-’n’-crookery.

Looking back, I do have some residual fondness for DiCaprio’s Howard Hughes in The Aviator, the star-fucking, illness-phobic billionaire coming off like a conceited teen idol going slowly to seed. (I’m sure Leo wasn’t drawing from life.) But it’s in the genre-bending madhouse thriller Shutter Island that the actor truly finds his groove, wallowing in Fibonacci-spiraling sadness and shame, and coming out the other side wearing all the moral/mental grime like a tailored suit.

Shutter Island (the closest Scorsese has gotten to the phantasmagorias of his beloved Michael Powell) marks the beginning of a fruitful late period of fiction features, documentaries, and television dabbles. Yearning spiritual quests (George Harrison: Living in The Material World and Silence, brothers from a Virgin Mother) bump up against blithely slippery bacchanalias (the momentum-whiplashing Wolf and the feature-length Vinyl pilot, a wonky script about the ’70s music industry given an apocalyptically adrenalized charge), though Scorsese’s gaze is across-the-board sober and incisive, even when the Mercer Arts Center is in literal free-fall. He saves the slosh for his second collaboration with Lebowitz, the mordantly funny and tacitly elegiac Netflix series Pretend It’s a City, in which his unbridled guffaws act as their own intoxicant, a hard-won mirth that’s the discernible result of an art-life less ordinary.

[Visit the “Complete” index here]